The Clash of the Soviet and Turkish Intelligence Services in 1920s Adjara: The Case of Mahmud Celaleddin

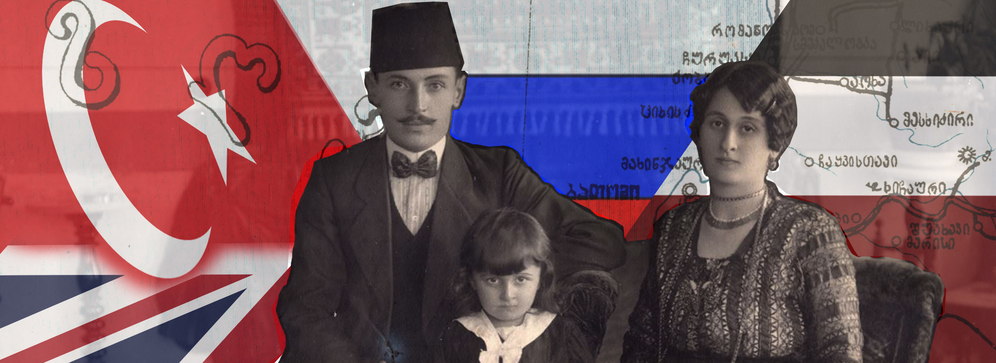

Contemporary Georgian historiography with respect to the modern and recent history of Adjara is to a great extent conservative, and rarely goes beyond certain bounds. The dominant narrative, which is extensively romanticized, is generally constructed around the themes of the forceful Islamization of a region controlled for a long period by the Ottoman Empire and the reunion of its population with the motherland at the first opportunity, after much longing and amid much joy. As the actors in this narrative we encounter the local pro-Georgian elite, in the form of the Committee for the Liberation of Muslim Georgia, while the local population are generally presented as passive, and external factors which played an important role in the formation both of Islamist/pro-Turkish and of pro-Georgian attitudes are to a great extent disregarded due to contemporary geopolitical and diplomatic considerations, which significantly obstructs the formation of a complete impression of the region’s history. Archive materials, Georgian, Turkish, Russian, and western periodicals from this period, and a small amount of research carried out largely beyond Georgia’s borders provide an entirely different picture of the subject: we see from these that, prior to the region’s full integration into Georgia, it was the arena of a large-scale ideological clash between various political factions. This ideological clash simultaneously had an international aspect, in which the intelligence services of both the Soviet Union and Turkey played an important role. Archive documents show us that several important figures from those political factions active in Adjara at the time were linked directly with the Soviet or Turkish intelligence services, and that these links often exerted a great influence on the policy pursued by regional or central authorities in relation to the region. As such, when seeking to understand the dynamics of the political processes in progress in Adjara in the 1920s, studying the actions of the intelligence services and the operations conducted by them holds considerable potential for filling a number of gaps in this span of the region’s history. The subject of this article will be the history of one network linked with the Turkish intelligence services in which an important role was played both by local Adjarians, and by the former Turkish Army officers Mahmud Celaleddin and Behçet Hamdizade, who held the position of secretary of the Adjarian Islamic Assembly, known in Georgian historiography by the name Sada-yi Millet, and whose unmasking, as archive documents indicate, gave rise to serious mistrust between the Revolutionary Committee of Adjarastan and the republican authorities as well as the Communist Party centre.

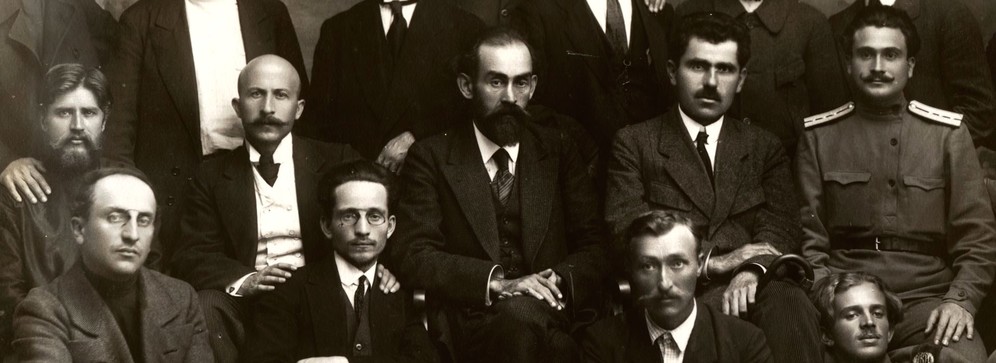

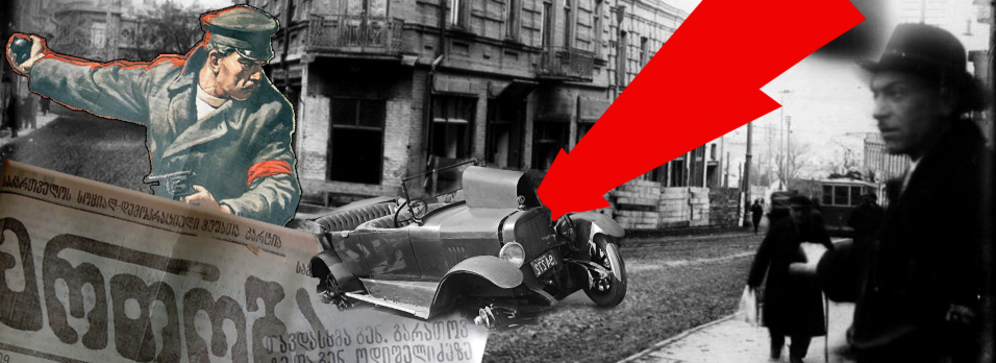

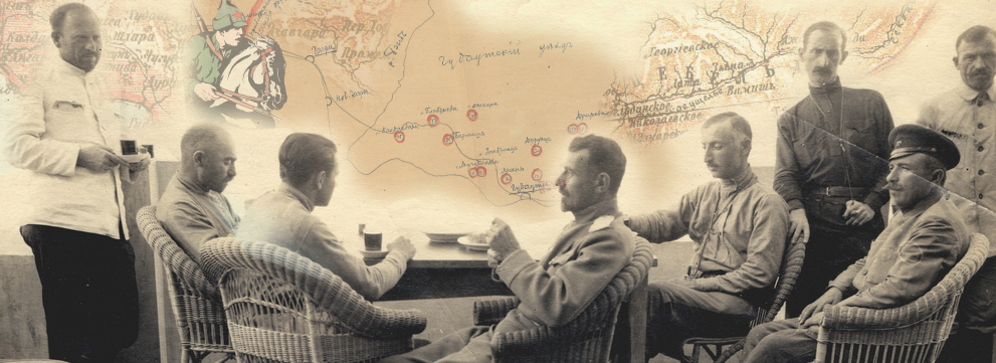

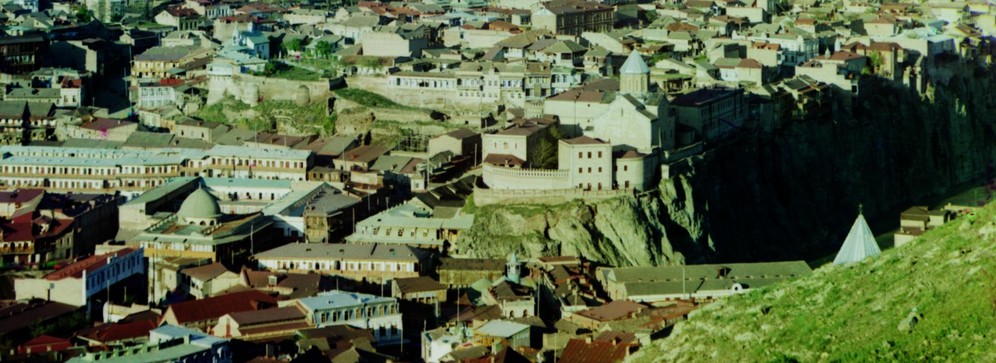

In the 1920s, Adjara and primarily the city of Batumi both played an important role in political life and represented an important border and transit point between the Soviet Union and Turkey. In addition, Batumi and to an extent Adjara as a whole were the arena of a serious political clash during this period which had an internal aspect – in Adjara, and particularly in its mountainous areas, feudalism was still strong, as, to a certain extent, were Islamism and pro-Turkish attitudes, which had their basis not so much in matters of ethnicity as in Islamist and monarchic motivations. There was opposition between the members of the old Meclis on one hand, who during the period of the First Republic had largely been supporters of the Georgian authorities, and a group known due to their newspaper Sada-yi Millet [The Voice of the People] as the “Sada-yi Milletians”, or as “the Meclis” or, more officially, by the names The Adjarian Islamic Assembly, The Batumi Islamic Assembly, and Cemiyet-i İslamiye, on the other. Good use of this situation was made both by the Soviet authorities and by Turkey. Despite the officially friendly relations that existed between these two states, both were in fact actively attempting to co-opt the local population, in the first case to strengthen Soviet authority, and in the second to bring the region under Turkish rule. A majority of largely co-opted Sada-yi Milletians was ultimately selected to the Adjarian Revolutionary Committee, a considerable number of whom continued to maintain links with the authorities in Ankara and to collaborate actively with the Turkish intelligence services.

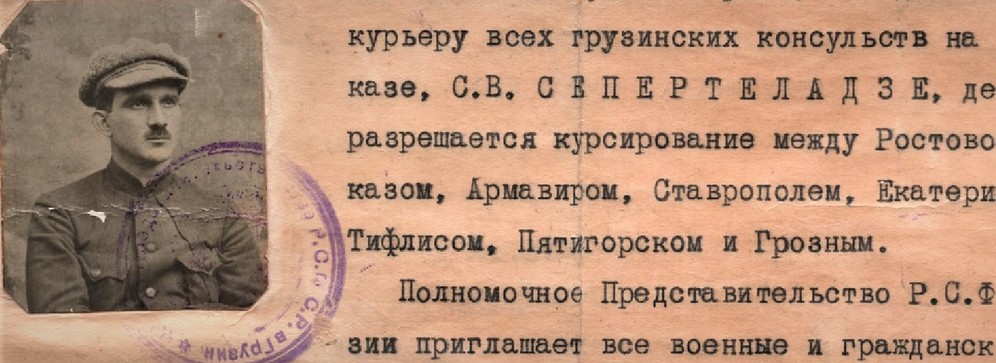

Among the members of Cemiyet-i İslamiye were official employees of the Turkish intelligence services. For example, research based on documents held in the local archive of the Mudanya District of Bursa Province provides us with information about a recipient of the Medal of Independence (İstiklal Madalyası) named Süleyman Sırrı Efendi, who was originally from Keda, located to the east of Batumi. This individual served in the Islamic police during the occupation of Batumi, then remained in the city and during this time joined Cemiyet-i İslamiye and continued actively collaborating with the Turkish intelligence services, acting as a courier between the Meclis and Turkish Army leaders Kâzım Karabekir Pasha and Halid Pasha.[1] As an important centre, Batumi was also the seat of the representation of the International Bureau of the Turkish Communist Party, which was a key congregation point for Turkish communists located in the Soviet Union and, despite the officially declared friendship between the two nations, was simultaneously a significant locus of conflict between their intelligence services.

Turkish migrants acting on behalf of the Turkish communists in fact represented a highly diverse group, which included both genuine communists as well as former supporters of Enver Pasha and migrant workers for whom enlistment in the Communist Party constituted a certain form of legitimization of their residence in the Soviet Union. Among them were well known figures; it was in the Batumi branch of the Turkish Communist Party that the once prominent Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet was active, who described this period in his autobiographical novel Yaşamak Güzel Şey Be Kardeşim [Life’s Good, Brother]. The migrants also included figures who either were or were believed to be employees of Kemalist Turkey’s intelligence services. Although for various reasons, the Soviet authorities initially preferred largely to turn a blind eye to the activities of these individuals, as they consolidated power and succeeded in co-opting figures with pro-Turkish attitudes (for example, appointing the influential Sada-yi Milletian Takhsim (Hasan Tahsin) Khimshiashvili to the position of Chairman of the Adjarian Revolutionary Committee), they also began devoting significant time to identifying employees of the Turkish intelligence services and expelling them from the country. Süleyman Sırrı Efendi, for example, was forced as early as 1921 to flee to Turkey,[2] while the Batumi branch of the Turkish Communist Party, which following the murder of the party’s leaders[3] was to a great extent scattered, was forced to reform itself as a section of the Georgian Communist Party.[4]

At the same time, in the context of the co-opting of the Sada-yi Milletians on one hand and their policy of collaboration with the newly formed Turkish Republic on the other, the Soviet authorities pursued a comparatively loyal policy toward some of those individuals with links to the Turkish authorities and, despite their being kept under active surveillance, the Cheka preferred to refrain from undertaking active measures against them until an advantageous moment presented itself. As the Soviet authorities in Adjara grew stronger, however, they began to actively criticize former Sada-yi Milletians, and as the position of the latter grew weaker, the Soviet authorities began active measures against Turkish communists and real or suspected agents of the Turkish intelligence services and their local contacts.

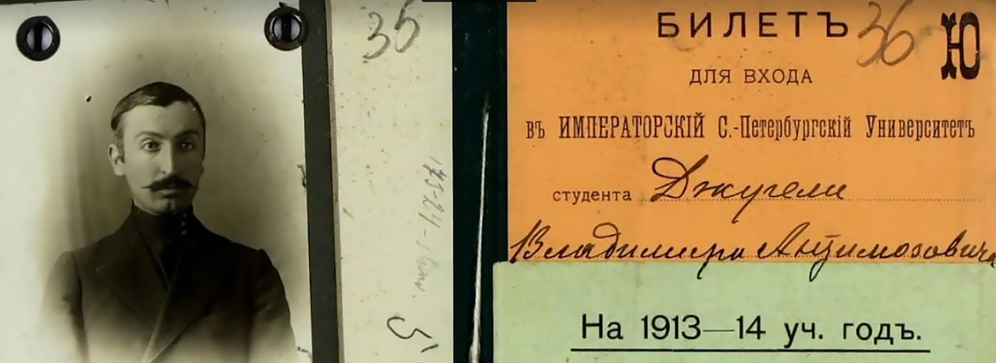

One such figure was Mahmud Celaleddin Bey, an Egyptian Arab by origin and delegate of the Baku Congress of Eastern Peoples, former Ottoman Army officer, and close associate of founder of the Turkish Communist Party Mustafa Suphi who wrote for his newspaper Yeni Dünya [New World].[5] He had served as an interpreter for Enver Pasha in Afghanistan and shared lodgings with him and other leaders of the Young Turks in Baku. We find information about him in file No. 24348, collection six of the Archive of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia.

The events in question began in May 1923, when the Batumi department of the Cheka in Adjarastan received information from an agent codenamed “Ali” that “an agent of Said Pasha”,[6] Mahmud Celaleddin, had travelled from Batumi to Tbilisi, and was staying at a house on Shepelevsky Street which, due to the political past of its owner, Feyzullah Vasadze, was most likely under active surveillance.[7] The agent’s attention had also been drawn by the fact that Mahmud Celaleddin, who officially made his living by selling lamp oil and operated in Batumi as a petty trader, had spent a lot of time in Tbilisi in Alexander Gardens, where he had often been seen with a group of individuals with links to the Turkish intelligence services and military pasts whose members regularly visited such figures as the Azeri consul Efendiev, prominent Adjarian member of the old Meclis Memed Abashidze, and others. He had also often been observed in the office of the Batumi Islamic Assembly, known more widely as Sada-yi Millet, which was greatly active in Adjara and had Islamic and Turkophile leanings, and had often visited the building of the Hotel Islam in Sheitan Bazaar, which was known to be a headquarters for figures linked with the Young Turks. The operative intelligence also reported that Mahmud Celaleddin had from as early as the period of the Libyan War[8] participated actively in Ottoman military intelligence activities, and had personally fought in Libya[9] alongside Enver Pasha and the Ottoman Consul in Batumi, Ibrahim Tali Bey.[10]His activity in the Caucasus was linked with the influential representative of the Young Turks, Baha Said,[11] on whose direct instructions Mahmud Celaleddin had become close with the Turkish Communist Party leader Mustafa Suphi and begun actively collaborating with communist organizations.

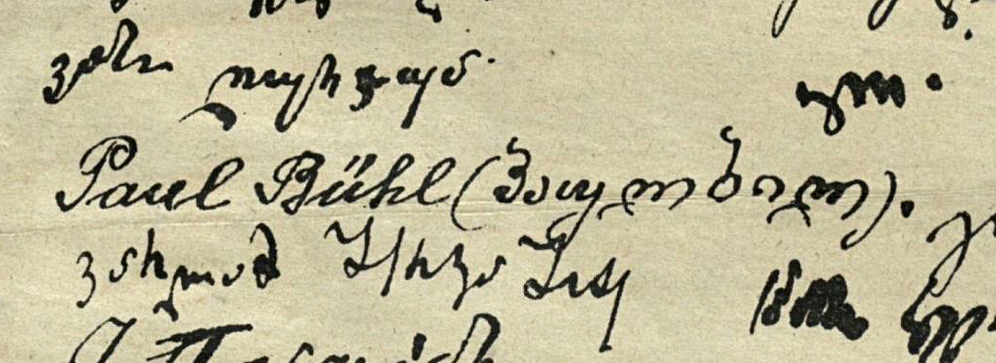

Ali Said Pasha

With such a situation leaving no time for hesitation, the Cheka urgently arrested Mahmud Celaleddin himself, the owner of the house where he was staying, Feyzullah Vasadze, Akper and Latif Akhmedov, in whose trading establishments Mahmud Celaleddin was often seen, former Ottoman Army officer Osman Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade, and another former Ottoman Army officer, madrasa teacher, and secretary of Cemiyet-i İslamiye,[12] Behçet Hamdizade.[13]

Although the Cheka began actively interrogating the detainees, each of them went to great efforts to vindicate themselves. Mahmud Celaleddin declared himself to be a genuine communist political refugee, and that any of his actions that might have appeared suspicious were linked with his desire to return to Turkey, and that he had neglected many aspects of his life for that reason. The Akhmedovs and Vasadze sought to convince the investigation that they had only a commercial association with Mahmud Celaleddin, who was a petty trader in lamp oil and related goods. Only Behçet admitted to having conveyed a letter to the Ottoman consul in Tbilisi, Husamedin Efendi, on behalf of the leader of the Meclis, and to having travelled to Turkey, although he added to this that he had not been able to stay in Hopa for long, as the Turkish authorities had intended to detain him as well.[14] Osman Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade, who was detained with them and who, according to the Cheka’s information, was a former officer of the Turkish Army with influential contacts in Ankara who was also posing as a member of the Turkish Communist Party, did not admit to his charges either, and claimed simply to be an acquaintance ofMahmud Celaleddin whom he likewise knew through trading activities.[15]

The Cheka held a different view, however. From their reports and the questions asked by them during the interrogations, we see that they believed Celaleddin as well as Behçet and Osman Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade to be individuals with active links to the Ottoman secret services. Their chief piece of evidence against Celaleddin was a meeting that had taken place in the house of Feyzullah Vasadze, where Celaleddin had made the acquaintance of a Cheka agent, Khudyakov – who was disguised as a Dagestani Doctor, Mehmed Agha – and had among other things revealed to him in conversation that he was a Turanist who collaborated with such figures with links to the Young Turks’ intelligence services as Nihad Bey Khimshiashvili and Nuri Bezhanidze. He had added that members of the Turkish Communist Party had been invited to Turkey because their physical elimination had been planned;[16][17] Mahmud Celaleddin had also stated with pride that he personally knew such figures as Enver Pasha.

Similarly, despite his testimony, in which he claimed to have become secretary of the Meclis only out of financial necessity, Behçet Hamdizade too was deemed by the Cheka to be a courier working for the Turks, and linked with the conveying of a letter from Meclis chairman Osman Gegidze to Cemal Pasha and the bringing to Adjara of directives from an Erzurum circular published by the authorities in Ankara and the communication of these to local pro-Turkish forces[18]. The Cheka’s suspicions were also aroused by the fact that Mahmud Celaleddin lived an extremely frugal life, despite his contacts. To this was added operative intelligence from an Investigator Piastopoulos (who also figures in the case as a translator who translated the Ottoman/Turkish case materials into Russian) which laid the blame upon another of the detainees, Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade, for the Ottoman Army’s massacre of the Greek population in Samsun. The attempts of the detainees to convince the Cheka of the reality of the guises behind which they lived and acted consequently proved futile. Neither did petitions written by family members have any effect, nor Russian-language notes among the case materials in which Mahmud Celaleddin congratulates Cheka personnel on the anniversary of the Russian Revolution.

The detainees ultimately began to pass ever more information to the Cheka. Mahmud Celaleddin claims in one of his pieces of testimony that the doctor (Khudyakov) had introduced himself as a representative from the Turkish mission and promised him assistance with his plans to resettle in Turkey. To this he added that he had the right to relocate to Central Asia and Afghanistan, which essentially confirmed the Cheka’s suspicions. He also stated that Nihad Khimshiashvili had close ties with one of the leaders of the Young Turks, Talat Bey,[19] while in relation to his own activities in Batumi he stated that Takhsim Khimshiashvili of the Council of People’s Commissars was fully informed of his actions.[20] Neither were Celaleddin or Behçet assisted by the Cheka’s success in procuring a witness against them. This was Ottoman Army captain and former prisoner of war, inhabitant of the village of Agara, and teacher Hafiz Ali Ibrahim, who admitted to being acquainted with Behçet as a colleague and added that he did not trust Mahmud Celaleddin.[21] When further interrogated, Hafiz Ali Ibrahim informed the Cheka that he had information that Mahmud Celaleddin had accompanied Fahri Pasha[22] in Afghanistan as an interpreter and assistant, and said that he was unable to understand after why, after all of this, Mahmud Celaleddin lived in such poverty and why he was not engaged in intellectual work, all the more so considering that he already had experience working as a teacher in Nakhchivan.[23] Osman Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade also confirmed that Mahmud Celaleddin had a good knowledge of foreign languages, and especially of Farsi.[24]

Following these pieces of testimony, Mahmud Celaleddin admitted to his links to the Turkish consulate in Tbilisi and to the Cheka agent Khudyakov, in his guise as the Dagestani doctor. Despite this testimony, however, we see in their records that the Cheka remained unsatisfied. Although it was studied a great deal, a letter that was discovered in Celaleddin’s possession and was believed to have been written in code had proved impossible to decipher, even, among other places, in Moscow, where it was examined in detail. In addition, their shared, predominantly hostile attitude with respect to west European countries meant that relations between the Soviet Union and Turkey were so close in 1921 that the Soviet authorities preferred to turn a blind eye even to the murder of Turkish Communist Party leaders by individuals close to the authorities in Ankara.

In this context the Cheka examined the case once again and made the decision to release Hafiz Ali Efendi and Feyzullah Vasadze. Akber Akhmedov was determined to hold Turkophile and anti-state views. Although no evidence was discovered to confirm the charges against Osman Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade, in the light of his past the Cheka deemed it justified to keep him detained. The investigation concluded based on the evidence gathered by it that Behçet Hamdizade’s charge under Article 59[25] had been proven.

The Cheka subsequently interrogated Behçet and Mahmud Celaleddin once more. Behçet did not hesitate to name the members of Cemiyet-i İslamiye, adding that he was to follow them to participate in the Kars Conference. With regard to the selection of the delegates, he stated that this had been done locally without the intervention of the consulate or the Turkish side.[26]

Mahmud Celaleddin, against whom quite considerable evidence had supposedly been gathered, named the group of former Ottoman Army Officers with whom he had come to Batumi and stated that he had made contact with Nihad Bey, who was acting against members of the Musavat Party among the Azeri authorities,[27] and that in doing so, he was hoping to contribute to the consolidation of good relations between Turkey and the Soviet Union. He stated that he was in Trabzon on the personal directives of Mustafa Suphi in order to gather delegates for the Congress of Eastern Peoples, and had himself been selected as a delegate representing the baqqals (grocers). As the reason for his undertaking trading activities he named material hardship. Celaleddin this time admitted that he had stayed in shared lodgings in Baku with Consul Taal Bey and Enver Pasha,[28] and also admitted to knowing Abdurreshid Efendi[29], who was a well known figure in Turkey, and that it was from him that he had received Chinese business cards discovered by the Cheka during a search. The Cheka believed the Chinese cards to be correspondence in code, although they were unable to assemble genuine evidence to this effect.

Following this it appears from the case that, despite the Cheka’s attempts to prove the charges, and to do so in such a way that this did not damage Soviet-Turkish relations, they were unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the Cheka were to a great extent convinced as to the culpability of Celaleddin and his companions.

The Cheka ultimately sentenced Behçet Hamdizade to punishment in the highest degree: that of execution together with confiscation of his property. Due to an absence of direct evidence, Mahmud Celaleddin and Osman Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade were sentenced with deportation to Turkey. Akper Akhmedov was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment, while Latif Akhmedov was permitted amnesty due to her age and social standing.

Behçet’s sentence was not carried out, however. The case file contains no documentation associated with a review of the case or reasons for alteration of the decision reached on legal grounds, which leads us to suppose that the case was decided at the level of the USSR’s central authorities. In a document dated 29 January 1925 we see that Behçet Hamdizade was also sentenced with deportation to Turkey. Çalıkoğlu/Çalıkzade, Behçet, and Celaleddin were transferred to the Turkish authorities on 25 February 1925.

Following this, traces of these individuals in Georgian and Soviet sources for the most part disappear. Why individuals who at first glance appeared to be high-ranking employees in Turkish intelligence were transferred to the Turkish side, despite one of them having been sentenced to punishment in the highest degree, remains unknown to us, although we might suppose that the reason lay in the friendly Soviet-Turkish relations of this period; Atatürk’s works were widely published in the Soviet Union at this time, while the Soviet political and cultural elite viewed Turkey as a progressive ally governed by authorities which had come to power as a result of a national revolution of liberation. An interesting example of such attitudes is provided by the writings of the diplomat Astakhov, who published works that were of an extremely apologetic nature toward Turkey.[30] It is highly likely that the Soviet Union was reluctant to make public a scandal associated with intelligence activity and, on the request of the Turkish authorities or of its own volition, elected to deport the suspects to Turkey rather than conduct a widely discussed trial and administer a strict punishment.

Neither do we know whether, following their return to Turkey, the accused continued their relations with the Turkish Communist Party, or whether they found themselves caught up in the waves of political repressions known as the Komünist Tevkifatları that were conducted against it. As these subjects have been quite well researched, however, there is quite a strong possibility that this question could be determined with reference to Turkish archival sources. As for the question as to whether Behçet or Mahmud Celaleddin operated under their real names, this too is left open by the Cheka, although taking into consideration that in the associated documentation and interrogation reports we see no information that the Cheka expressed doubts in relation to the true identities of the accused, the possibility of this is quite high.

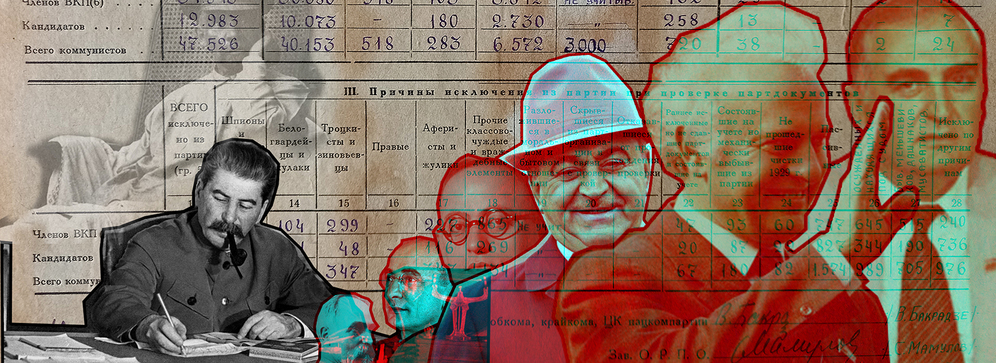

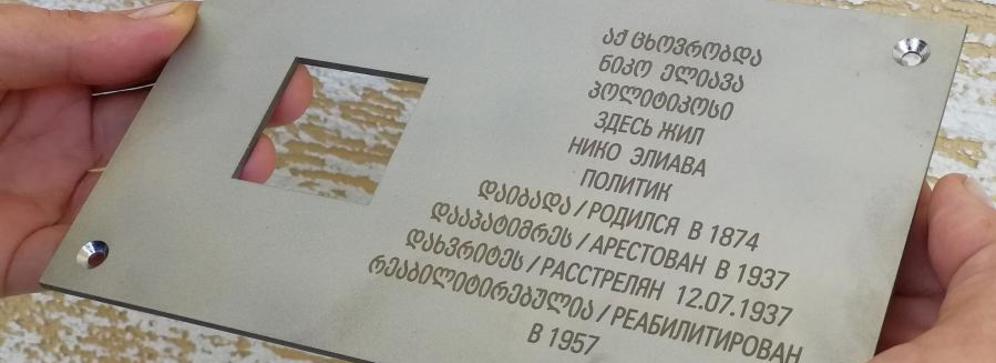

As Turkish influence in Soviet Georgia grew weaker together with the networks of the Turkish intelligence services, a large number of those members of Itihad Islam/the Batumi Islamic Meclis (Sada-yi Millet) remaining in the country opted to collaborate with the Soviet authorities, although, as a result of this case and others, their position rapidly began to weaken. At the 1924 Georgian Communist Party Plenum, Amberki Urushadze sharply criticized Takhsim Khimshiashvili and spoke especially about the elimination of “deviations” in Adjara, among which the Turkophile “deviation” was characterized as one of the most significant, and Khimshiashvili and his deputy and subsequently his replacement, Memed Ghoghoberidze, mentioned among its leaders.[31] The following year it was the turn of Sergo Orjonikidze to directly and openly criticize Takhsim Khimshiashvili of preserving feudalism in Upper Adjara, and of a deficiency of vigilance in his party and of creating his own cult, although he refrained from making radical declarations and only emphasized Khimshiashvili’s “urgent need for political re-education”.[32] While it is true that Takhsim Khimshiashvili and those who shared his views were able to retain power for a time, it was clear that their influence was approaching its end and that, in the light of the evidence at hand, it was only a matter of time until their dismissal from their posts and punishment under either Party disciplinary procedures or criminal law. To this was added the gradual tightening of border controls by the Soviet central authorities, which made contacts with Turkey significantly more difficult. This provided the Soviet authorities with the opportunity to appoint personnel whom they considered more reliable. Ultimately, following the uprisings of 1929, many Adjarians linked to the uprising and several beys and religious figures, as well as every Sada-yi Milletian, were forced to seek refuge in Turkey, while those who remained for the most part fell victim to the political repressions of 1937-38. Secularization and the disappearance of the political influence of the old elite largely brought the existence of the Adjarians as a group in which a world view based on religious identity was quite influential to an end. While it is true that, due primarily to Islam and autonomous governance, the Adjarians preserve a certain regional difference, in post-Soviet Adjara the process of assimilating national identity is to a great extent complete, and Islam-related matters are generally considered only in a religious context.

We can conclude from this study that the modern and recent history of Adjara comprises several conflicting dynamics in which the interests of both local and significant regional players in many cases actively intersected. As for the attitudes of the regional elite, these were to a great extent determined by their personal political and economic interests, while pro-Georgianism, Islamism, and pro-Turkism were but a nominal factor. This is readily apparent in such details as the members of the Committee for the Liberation of Muslim Georgia’s situation-based collaboration with both pro-Turkish/Islamist forces and the Soviet authorities, or the mass entry of former Sada-yi Milletians into the Communist Party. Much was furthermore dependent on the support of external forces. The organized aspect of Islamist/pro-Turkish discourse was largely lent to it by the support of the Turkish intelligence services, while the camp that opposed it was closely dependent on the intelligence services of both independent Georgia and the Soviet Union. Intelligence services played an important role in clashes between the camps and here, both the Soviet and the Turkish sides actively made use of the oppositions, that were largely of a feudal nature, between local elites that continued to exist until the consolidation of Soviet authority. The opposition between the Abashidze and Khimshiashvili clans, for example, had turned into a sort of “international” confrontation in which, despite widespread views that the Abashidzes were “pro-Georgian”, and the Khimshiashvilis “pro-Turkish”, this was in fact a matter of rapidly changing political alliances and a classical Machiavellian politics in which the main prize was not promotion at the Georgian or the Turkish court, but regional dominance. The interests and identity of the broad masses of the people were for their part formed to a great extent around regionalism, religion and traditions, in considerable contrast with the situation that exists in the region today, and were actively prone to any form of manipulation or social engineering by any political force. Thus, study with reference to primary archive sources of the dynamics in progress in the region in the 1920s-1930s, including the role in this of the intelligence services, holds very considerable importance for examining and achieving a proper understanding of Adjara and its population’s contemporary identity and overall status.

Translated by Geoffrey Gosby

Referenced Works

Kardam, Ahmet – Mustafa Suphi: Karanlıktan Aydınlığa [Mustafa Suphi: From Darkness to Light], İletişim Yayınları, Istanbul, 2020

Sada-yi Millet [The Voice of the People], No. 82, 13 December, 1919

Tokgöz, Sedat – Emniyet Genel Müdürlüğü Arşiv belgelerine Göre Polis Memuru Torunizade Süleyman Sırrı Efendi [Police Officer Torunizade, Süleyman Sırrı Efendi according to Archive Documents of the General Directorate of Security], Pamukkale University, Master’s Thesis, Denizli, 2011

Tunçay, Mete; Akbulut, Erden – Türkiye Komünist Partisinin Kuruluşu (1919-1925) [The Founding of the Turkish Communist Party (1919-1925)], Yordam Yayınları, Istanbul, 2021

Astakhov, Georgij Aleksandrovich – Ot sultana k demokraticheskoi Turtsii: Ocherki iz istorii kemalizma [From the Sultan to Democratic Turkey: Sketches from the History of Kemalism], Moscow; Leningrad: Gos. Izd-vo, 1926 (M. : tip “Krasnii proletarii”)

tavisupali sakartvelo [Free Georgia], No.3, 15 July, 1921

The Archive of the Georgian Communist Party, 1921, c. 14, dossier 1, v.4, file 119

The Archive of the Georgian Communist Party, c. 14, 1925, dossier 2, file 350

The Archive of the Georgian Communist Party, c. 14, 1924, dossier 2, v.1, file 914

The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348

[1] Tokgöz, Sedat – Emniyet Genel Müdürlüğü Arşiv belgelerine Göre Polis Memuru Torunizade Süleyman Sırrı Efendi [Police Officer Torunizade, Süleyman Sırrı Efendi according to Archive Documents of the General Directorate of Security],Pamukkale University, Master’s Thesis, Denizli, 2011, p.37

[2] Tokgöz, 2011, p.42

[3] This refers to murders that took place on 28 January 1921 on a ship sailing on the Black Sea, when individuals with links to the Turkish intelligence services killed Turkish Communist Party General Secretary Mustafa Suphi and party leaders accompanying him – a total of 14 people (for details, see footnote 17)

[4] Tunçay, Mete; Akbulut, Erden – Türkiye Komünist Partisinin Kuruluşu (1919-1925) [The Founding of the Turkish Communist Party (1919-1925)], Yordam Yayınları, Istanbul, 2021, pp.149-152

[5] We find one of his articles, in which he blames the Armenian and Turkish bourgeoisie for the Armenian Genocide, in Ahmet Kardam’s biography of Mustafa Suphi. See: Kardam, Ahmet – Mustafa Suphi: Karanlıktan Aydınlığa [Mustafa Suphi: From Darkness to Light], İletişim Yayınları, Istanbul, 2020, p.262

[6] Most likely meant here is Ali Said Pasha (Akbaytogan, 1872-1950), a Turkish military and political figure, chairman of the Commission for the Three Vilayets (Elviye-i Selase - Kars, Ardahan, and Batumi) from 1921-22, from 1922 Head of the Turkish Military Court, and from 1927 a general in the army and deputy in two convocations of the Turkish Mejlis. He was present in Batumi in February 1922.

[7] It is notable that the case mentions Feyzullah Vasadze as a trader and does not address her political activities; it is however highly likely that Feyzullah Vasadze was none other than a once considerably influential member of the Muslim Section of the Communist Party of Adjaristan. See: The Archive of the Georgian Communist Party, 1921, dossier 1, v.4, file 119, p.15

[8] Of the 1912 Ottoman-Italian War

[9] The Archive of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia, collection six, case No. 24348, p.7

[10] İbrahim Tali (Öngören) (1875-1952), a Turkish doctor, diplomat, intelligence officer, and politician who served as Turkish ambassador to Poland and Turkish consul in Batumi. He participated actively in military intelligence gathering and represented the Turkish government at the Congress of Eastern Peoples held in Baku in 1920. He was known for his anti-communist views.

[11] Baha Sait (1882-1939), a Turkish intelligence officer and one of the founders of the Guard Society (Karakol Cemiyeti). He participated actively in intelligence operations to support the authorities in Ankara in Entente-occupied Istanbul, and later conducted research in Anatolia investigating the political and cultural characteristics of various segments of its population.

[12] This organization is also referred to in Georgian sources by the name of its newspaper, Sada-yi Millet [The Voice of the People].

[13] Behçet Hamdizade worked as a teacher in the village of Angisa. The village’s madrasa notably figures in the newspaper Sada-yi Millet: in its 13 December, 1919 issue we find a statement sent in the madrasa’s name thanking the firm of Zosima Baranovich, Viktor Bey, and Yusuf Agha Varshalomidze for financial assistance. See: Sada-yi Millet, No. 82, 13 December 1919, p.2 http://www.osmanlicagazeteler.org/Oku.php?id=8109

[14] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.11

[15] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.66

[16] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.9

[17] It is certainly the case that Mustafa Suphi and individuals accompanying him, who had travelled to Anatolia at the invitation of the authorities in Ankara, were the victims of an attack by groups organized by the local authorities in Kars and Erzurum, following which the authorities in Ankara made the decision to deport them, and placed them aboard a ship at Trabzon. It was on this ship that Mustafa Suphi and his companions were murdered on 28 January 1921 by Yahya Kaptan, a figure close to the Ankara authorities, and those under his command, and their bodies thrown into the Black Sea. Due to the nature of Soviet-Turkish relations at this time, the USSR limited its response to a verbal protest.

[18] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.11

[19] Talat Muşkara (1880-1859), known by the nickname “Küçük Talat” (Little Talat) to distinguish him from Talat Pasha – a Turkish politician and intelligence officer who served as an intermediary between Enver Pasha in the Soviet Union and Mustafa Kemal. He was later engaged in commercial activity in Izmir.

[20] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.67

[21] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.55

[22] Ömer Fahreddin (Türkkan) (1868-1948) – a Turkish military figure and diplomat. He was given the title “the Defender of Medina” for courage shown in the defence of the city in the First World War and was a member of Mustafa Kemal’s staff. At the end of 1921 he was appointed Turkish ambassador to Afghanistan, where he served until 1926.

[23] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.77

[24] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.85

[25] Under the 1922 Criminal Code of the USSR, “collaboration with foreign states with the objective of bringing about a military intervention on their part” was punished with execution and the confiscation of personal property.

[26] The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.254

[27] This is an indication that Musavat and the Young Turks indeed disagreed on many matters and that members of Musavat took quite a negative view of Turkish attempts to interfere in their internal affairs.

[28]The Archive of the MIA of Georgia, collection six, file No. 24348, p.264

[29] Here is likely meant Abdurreshid Iskar (1857-1944), a Tatar religious and political figure who conducted missionary activities to spread Islam in Japan. Aburreshid was certainly present in the Soviet Union at the time of these events.

[30] See: Astakhov, Georgij Aleksandrovich, Ot sultana k demokraticheskoi Turtsii: Ocherki iz istorii kemalizma [From the Sultan toDemocratic Turkey: Sketches from the History of Kemalism], Moscow; Leningrad: Gos. Izd-vo, 1926 (M. : tip “Krasnii proletarii”)

[31] The Archive of the Georgian Communist Party, c. 14, 1924, d. 2, v. 1, file 914, pp.149-150

[32] Ibid., c. 14, 1925, d. 2, file 350, p.104