The Enrolment of the Georgian Orthodox Church in the Ecumenical Movement as a Tool of Soviet Policy

Introduction

The ongoing war in Ukraine and the position taken by the Russian Church with respect to it have motivated me further still to examine “Soviet religiosity”. The correlation between the available facts, which is in many cases readily evident, enables us to say quite simply that the position of the present-day Russian Orthodox Church clearly demonstrates how important a mechanism the church was in the Soviet period for achieving policy objectives, and that this narrative extends throughout Russian policy today.

It is important when analysing religious policy in the Soviet Union to consider each development, state of affairs, and decision within its broader context. The religious policy of the Soviet Union was defined throughout its existence by an atheistic narrative and antireligious propaganda. In 1962, in parallel to this policy-related discourse, those Orthodox churches within the Soviet Union became members of the World Council of Churches. What lay behind the enrolment of these churches in the Ecumenical Movement amid a strict antireligious policy, and how did these churches come to be instrumentalized during the 1960s? In this article will attempt to provide answers to these questions by examining the utilization of the church as a tool of policy, taking the enrolment of the Georgian Orthodox Church in the World Council of Churches as an example.

Black Cross on a Red Oval, Kazimir Malevich, 1921

Religious Policy under Khrushchev

An analysis of Soviet religious policy reveals various aspects by which it was defined throughout Soviet history. These included both an ideologized religious policy at a domestic level and a desire to further strengthen the Soviet Union as a globally hegemonic state at an international level. The religious question formed a constituent part of Soviet ideological policy, which at once encompassed politics, economics, and culture.

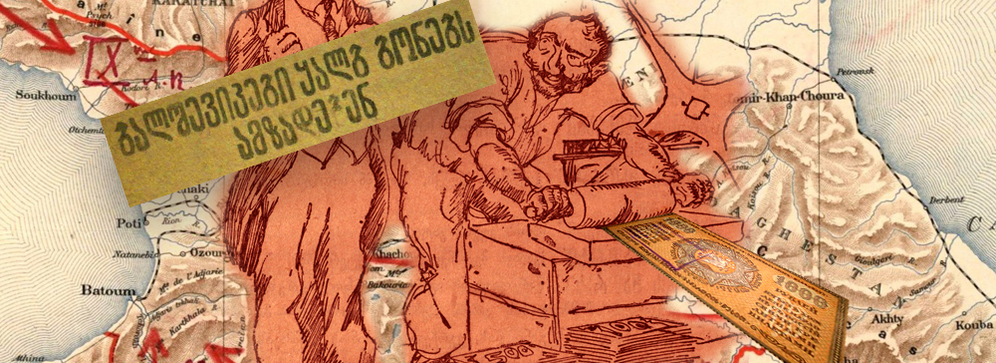

When examining the religious policy of the Soviet Union we can distinguish several phases. The first of these was a policy of annihilation of religion implemented under the “Red Terror”. Subsequently, in the period following the Second World War, Stalin conducted a so-called “policy of rapprochement and mutual cooperation”, which was manifested as a relaxing of antireligious policy. 1944 saw the creation within the Soviet Council of People’s Commissars of a “Council for the Affairs of Religious Cults”, led by a chairman and representatives from the Soviet republics, which was entrusted with a so-called “intermediary” role between churches (religious organizations) and the state.[1] Following the death of Stalin, Khrushchev attempted to return to the approach to religious policy employed in the 1930s, and initiated an antireligious and atheist policy in intensified form.[2]

In his book Religion, State and Politics in the Soviet Union and Successor States, John Anderson analyses how approaches to Soviet religious policy changed from one leader to the next and what internal and external factors influenced its implementation. Surveying religious policy in the period following Stalin, the author emphasizes that the approach adopted under Khrushchev was characterized by a renewed and energetic assault on religious organizations and ideas.[3]

A brief historical overview will permit us to analyse the broader context, the situation that existed in the Soviet Union with respect to religious institutions, and what important decisions preceded the enrolment of (Orthodox) religious institutions in the World Council of Churches. Speaking at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in 1956, Khrushchev communicated a clear message that it was essential religion should cease to exist for good. The official reason for a renewed assault on religion was given in clause one of the Resolution of the Central Committee of July 1954 “On major shortcomings in scientific atheist propaganda and measures to improve it”.[4] The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union declared that many Party organizations were unable to ensure adequate management of scientific atheist propaganda among the population, as a result of which important aspects of ideological efforts were effectively going unperformed.

The July 1954 resolution adopted by the Central Committee also states that increased activity on the part of churches had led to a rise in the number of citizens observing religious festivals, performing religious ceremonies, and undertaking pilgrimages to so-called “holy places”. Religious superstitions were reportedly undermining the consciousness of the Soviet people and diminishing their active participation in the building of communism.[5]

An emphasis was placed on religious policy once again in 1959, when the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences adopted the resolution “On the intensification of scientific work in the sphere of atheism” and subsequently created atheist divisions in various research institutes of the academy.[6] Khrushchev’s atheist policy was in its initial stage linked with the intensification of propaganda in the press, on television and on the radio as well as in educational institutions. 1959 saw the founding of the monthly atheist periodical Nauka i religiia [Science and Religion], while the daily press was charged with popularizing current scientific research.[7]

In addition to its local space, the Soviet Union also worked on the international stage. Representatives from the nomenklatura emphasized the notion of religious freedom and equality; Vladimir Kuroyedov, for example, who headed the Council for Religious Affairs from 1965, stated that: “It was explained…that, in accordance with legislation in force in the Soviet Union, the most important thing was assuring the equal principle of freedom of conscience for believers of all religious persuasions. Catholics in our country also enjoy the same rights as believers of other religions.”[8] Khrushchev’s antireligious and atheist policy had its results in every Soviet Republic: “Although clerics were apparently not directly persecuted, the security organs spread rumours and slander of all kinds concerning them with the objective of fully cutting off the church from society and locking it up within itself.”[9] On 15 March 1961, the Council for the Affairs of Religious Cults and the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church adopted the “Directive on the use of legislation with respect to cults”. This “directive” warned local bodies to ensure that every citizen’s rights were protected, and forbade them from using administrative measures (such as the closure of illegal places of worship) to oppose religion, interfering in the activities of religious organizations, or offending the feelings of the faithful;[10] it was however followed immediately with the statement that religious ceremonies would be permitted only if they did not violate social order or the rights of Soviet citizens.[11]

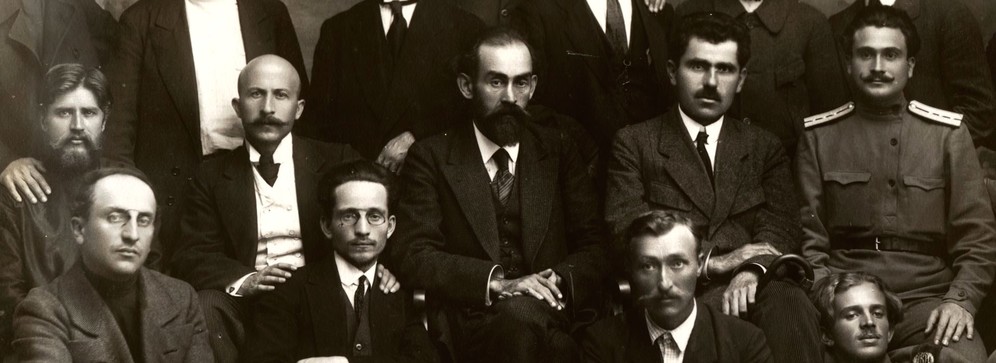

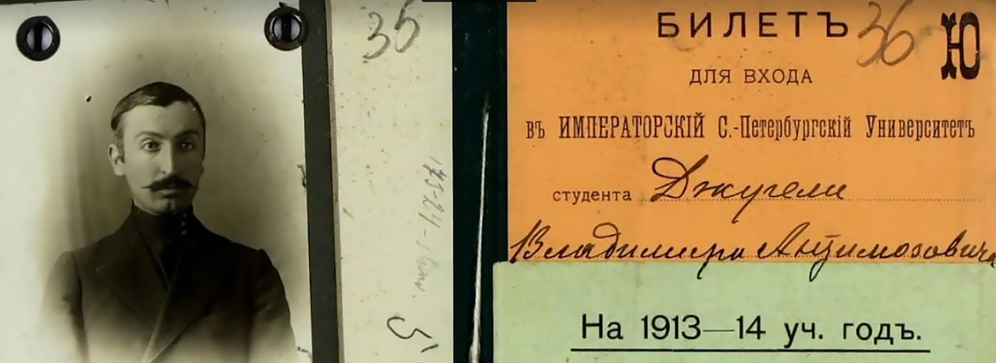

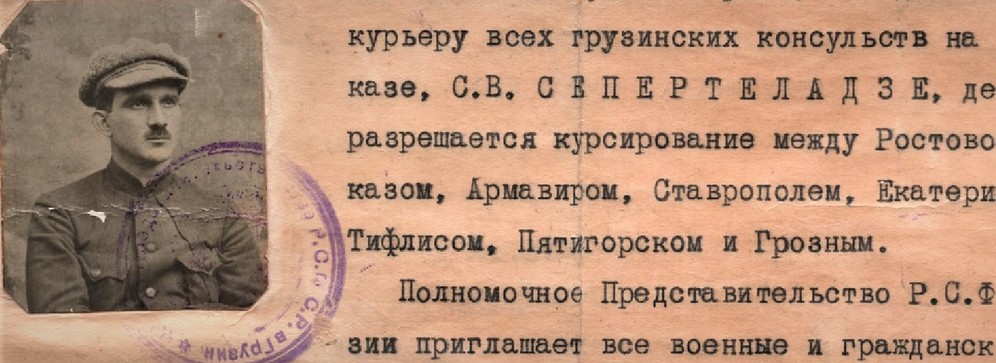

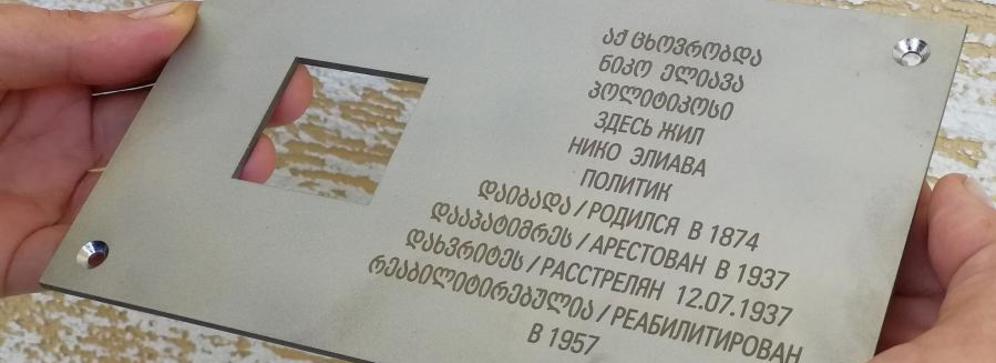

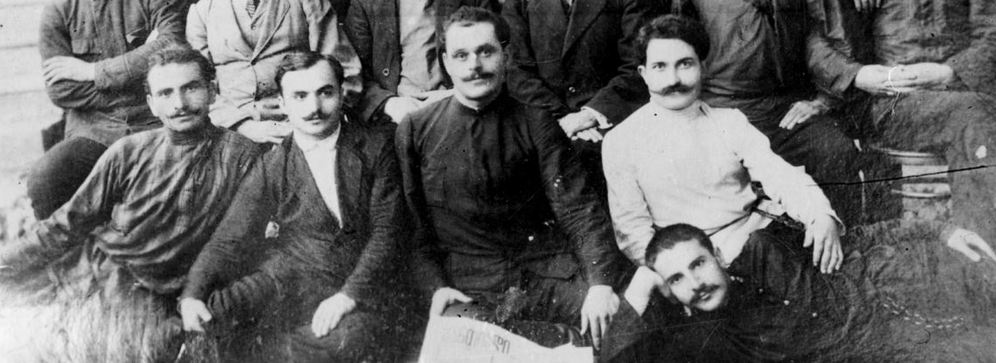

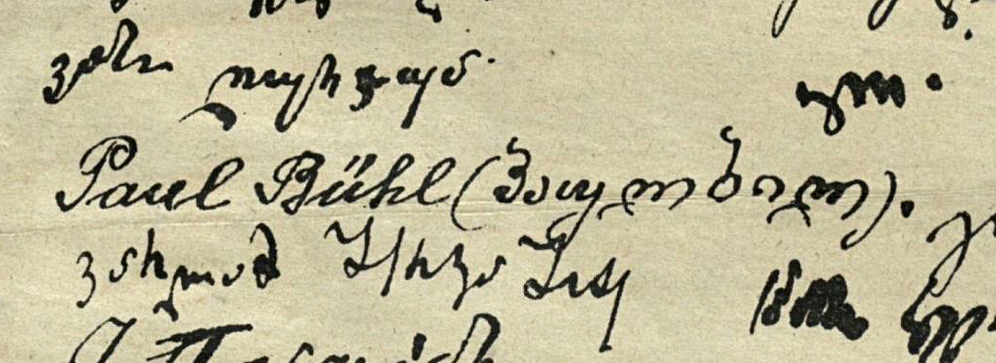

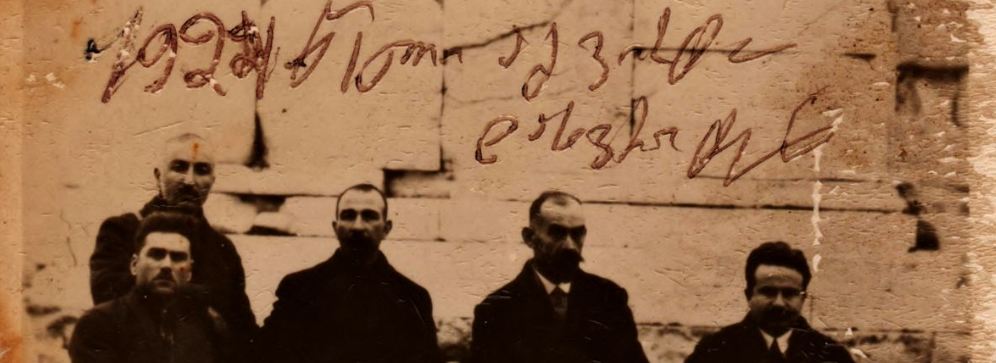

Reference to the document Crimes of Krushchev published by US Congress House of Representatives’ so-called “Committee on Un-American Activities” reveals the situation regarding religious rights in the years 1959-1960 to have been grave. Printed in the document is an interview with Givi Zaldastanishvili, vice-president of The Georgian National Alliance, editor of the English-language periodical The Voice of Free Georgia, and co-founder of the newspaper kartuli azri (Georgian Opinion), and Giorgi Nakashidze, who actively opposed the Soviet Union, was a member of the Prometheus Society founded in Warsaw in 1925, was invited to teach Georgian language at Warsaw University in 1933, and had been lecturing at Harvard University since 1948.[12]

In the interview, Givi Zaldastanishvili speaks about positions held with respect to religion, and about the fears that existed within religious institutions, stating that: “It is a challenge to the regime to attend church services. Ministers do not have the right to make sermons because of the danger of expressing anticommunistic thoughts.”[13] Asked whether religious freedom existed in the Soviet Union, he speaks about the history of the church, about the patriarchs, and about the policy of the Soviet Union with respect to religion, and finally concludes that “There is no freedom of religion in Georgia.”[14] On the subject of Khrushchev’s true objectives, Zaldastanishvili says that he peaceful statements were not to be believed, because the leader was engaged in a struggle against Western civilization. [15]

In the 1960s, in parallel with the Soviet Union’s ideological confrontation with the West, the platform of the World Council of Churches also existed, where the Soviet Union did not represent a dominant power because the churches in the USSR were not members of the Ecumenical Movement, although certain points of intersection with the World Council of Churches can be discerned at the end of the 1950s. In 1958, upon the initiative of the Czech Reformed theologian Josef Hromádka, an international meeting of church ministers took place which was attended by Christian groups and church representatives from both Eastern and Western Europe, the purpose of whose coming together was to undertake to perform an active and positive role in strengthening world peace; the participants in the meeting included Soviet delegates.[16] Subsequently in 1961 the Russian Orthodox Church, and in 1962 other Orthodox churches within the Soviet Union, became members of the Ecumenical Movement, despite the strict antireligious and atheist policy that was in place in the USSR.[17] The religious policy in effect meant that local churches had little opportunity to pursue independent contacts with the World Council of Churches; even following enrolment, not a single word was heard from representatives of Orthodox churches in the Soviet Union about existing problems, and speakers said nothing about internal difficulties.[18]

What was the main purpose of the Orthodox churches’ enrolment in the Ecumenical Movement? Stephen Jones discusses this question in his book Soviet Religious Policy and the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church, from Khrushshchev to Gorbachev, in which he argues that the enrolment of those churches within the Soviet Union in the Ecumenical Movement was fundamentally an attempt on the part of the communist nomenklatura to secure more places in the Central Committee of the World Council of Churches for the purpose of influencing its activities.[19]

Jones’ standpoint accords with that of J.A. Hebly in his article “The State, the Church, and the Oikumene: The Russian Orthodox Church and the World Council of Churches 1948-1985”, in which he contends that religious organizations were utilized as a political tool. For the Soviet Union, which had the objective of creating a godless society, the World Council of Churches represented not a forum where its members could exchange points of view, but rather a stage where the capitalist ideas of the West and the communist ideas of the East would oppose each other; in this opposition, church representatives were accorded the role of Party ideologues who would act at the World Council of Churches as representatives of reactionary forces.[20]

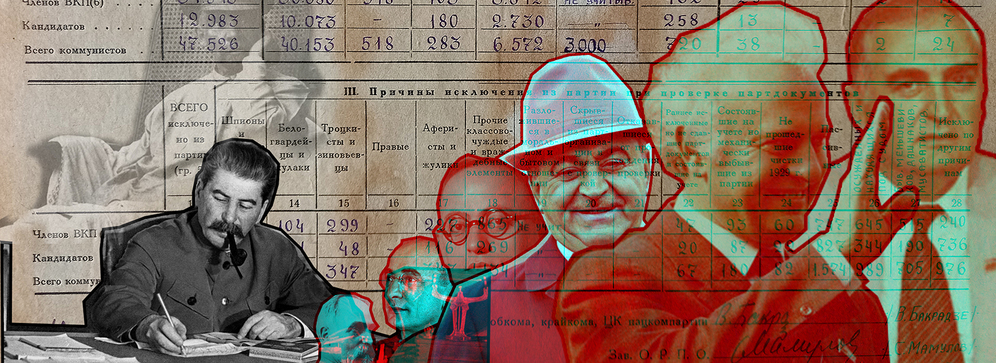

In the article “A survey of Soviet religious policy” published in 2005, P.A. Walters emphasizes that the mechanism adapted in the Soviet Union was to enable the security bodies to penetrate the structures of religious organizations and effect control of them. It is important also to emphasize the involvement of agents in conferences held by the World Council of Churches. A large number of delegation members sent by the Soviet Union were KGB agents; these included clergy and prominent church figures. Such agents were often presented by the KGB as “technical personnel”.[21]

A uniform approach existed in the USSR as to what the function of Orthodox Church representatives at the World Council of Churches would be. In his book Between Faith and Compromise, the Bulgarian historian Momchil Metodiev chronicles how the Soviet Union and its local puppets made global use of Bulgarian Orthodox figures in the World Council of Churches to support the USSR’s strategic objectives.[22] In Metodiev’s view, “The participation of the Bulgarian Church in ecumenical organizations was not inspired by the notion of interreligious dialogue and cooperation”, but, to the contrary, “ecumenical activities [as undertaken by representatives from the Soviet bloc] could be classified as a church within a church”[23]. In the author’s view, study of the communist archives provides further confirmation that various churches in the World Council of Churches followed the Soviet script during the Cold War.[24] “Even during the years of the Cold War, it was known that church representatives coming from communist countries had the obligation to report about their activities abroad to their country’s authorities.”[25]

The Georgian Orthodox Church 1961-1962

Following the Soviet Union’s pursual of a strict antireligious policy, by decision of the Soviet nomenklatura the Georgian Orthodox Church joined the World Council of Churches in 1962, and the phase of isolation from the Christian world came to an end. An analysis of archive documents enables a full picture to be conceived as to the conditions under which the Georgian Orthodox Church was obliged to exist. The struggle against religion proceeded on several flanks: together with the intensification of atheist propaganda, changes relating to an antireligious policy can also be noted in legislation.

A document in the Party archive dated 1959, “On the improvement of scientific and atheist propaganda by decisions of the Georgian Communist Party Central Committee”, discusses the existing achievements and challenges in Georgia as well as the significant work carried out to strengthen atheist education, although it is pointed out that serious shortcomings still remained in the production of antireligious propaganda, and that the republic’s Party bodies were only weakly opposing the various religious festivals that were held every year.[26] The Party archive also contains documents from the Department for Agitation and Propaganda concerning “propaganda in lecture form”, including memoranda compiled at a regional level as to how many lectures had been held relating to scientific atheist propaganda; one document includes the number of lectures held in the years 1961-1962 in various regions. Memoranda and reports were compiled by the heads of the departments for agitation and propaganda of the district committees of the Georgian Communist Party. In these documents, which include both narrative reports as well as notifications and memoranda, particular attention is devoted to the resolution of 5 May 1961 “On measures to select and train propaganda personnel”. The memoranda and reports were in most cases written for the head of the Department for Agitation and Propaganda of the Georgian Communist Party Central Committee, M.A. Gogichaishvili.[27] It is important here to emphasize the notion of an atheist education; this is quite removed from the concept of neutralizing religion and does not mean only the exclusion of religion from the public space; to the contrary, “it implied a coherent anti-religious “worldview” and an appropriate agenda for action without which Soviet society could not reach its ultimate – communist – developmental stage”.[28]

The Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was created in 1943 as part of the USSR Council of People’s Commissars, interfered unceremoniously in internal church affairs. Correspondence between the Georgian patriarchs and council representatives was primarily of a formal nature; the council left no space for free action, particularly in cases concerning the restoration of churches on the instructions of religious figures. In 1960, Catholicos-Patriarch Ephraim of the Georgian Orthodox Church was sent a letter from officials in religious affairs stating that religious figures had no legal right to take independent decisions without the consent of the local Soviet body.[29]

One mechanism for exercising control over the church was the taxation of clergy; some 87% of their income was taken by the state. Every clergy member’s involvement in the life of the collective was strictly monitored, as were every clergy member’s activities. Virtually every aspect of religious life was subject to close supervision and control by Party and state authorities.[30]

At a regional executive committee meeting held in 1961 attended by religious affairs official D. Shalutashvili and the secretaries of the regional executive committee, concrete deadlines for a census of churches were set.[31] Bishops paid income tax, and were charged a predefined sum. The financial department of the regional executive committee sent a report that included a list detailing the income tax status of the bishops of particular regions to an authorized representative of the Georgian SSR Council of Ministers.[32] During this period, a census of churches and monasteries, their property, and the income of their clergy took place; archive documents also include information about the monthly salaries of clergy in Tbilisi and other income of theirs.[33]

Analysis of archive documents reveals one-off records of religious organizations which describe the size of the institution, how many people were associated with it, whether or not it was registered, whether or not it had undergone an inventory of religious property,[34] and its situation with respect to the taxation of clergy.[35] According to the record, the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church at this time comprised five operational eparchies (with seven bishops and more senior clergy), and the patriarchate included 100 functioning churches and two convents and monasteries, and no more than 105 clergy. The church had no residence, no publishing house, and no seminary, and the historical autocephaly of the Georgian Orthodox Church was not recognized by the majority of the world’s Orthodox churches.[36]

In light of the full control exercised by the USSR over church activities, there can be little doubt that enrolment in the World Council of Churches was the result of pressure from the Soviet authorities.[37] In autumn 1947, with Stalin’s blessing the Moscow Patriarchate appointed a conference, and in 1948 the Eighth Pan-Orthodox Council took place. For the Soviet nomenklatura, the principal challenge of the approaching World Assembly of Churches was to diminish the international influence of the Vatican, which was viewed as the foremost enemy of the Soviet Union in the religious sphere; the position of the Soviet leadership with respect to the doctrine of Papal primacy, which elevated the influence of the Holy See in international affairs, was especially negative.[38] In accordance with the “Resolution on the Ecumenical Movement and the Orthodox Church” adopted in Moscow in 1948, Orthodox churches in the Soviet Union disassociated themselves from the World Council of Churches. According to the Orthodox churches, the objectives of the “Ecumenical Church” did not accord with the Christian ideal and the objectives of Christ’s Church, for the former sought by intensifying social and political activities to become an influential force on the international stage.

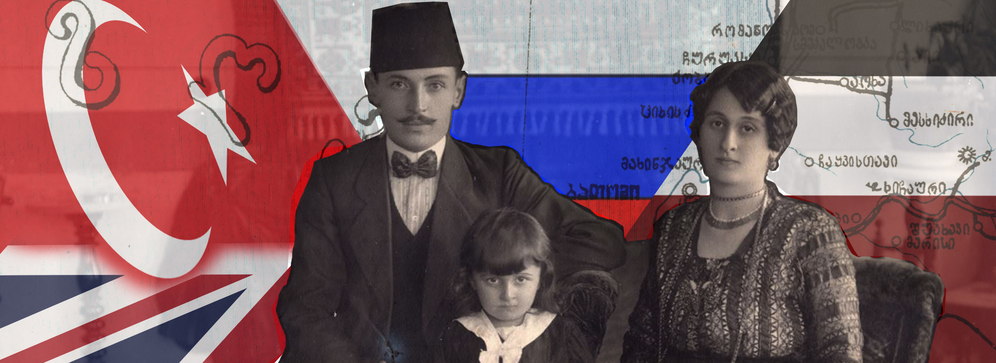

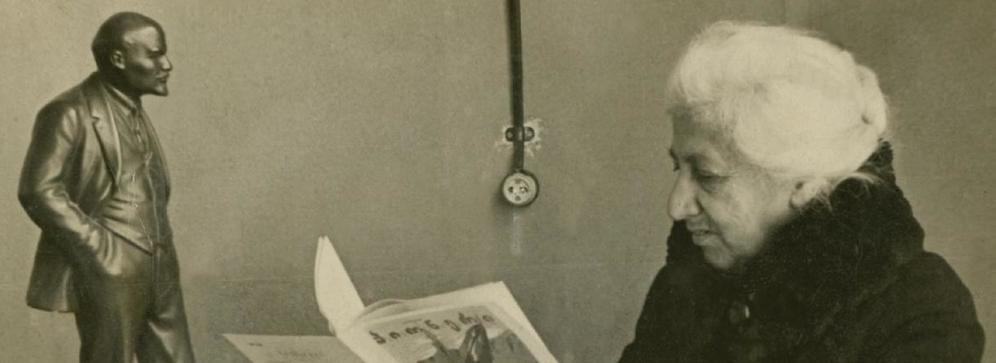

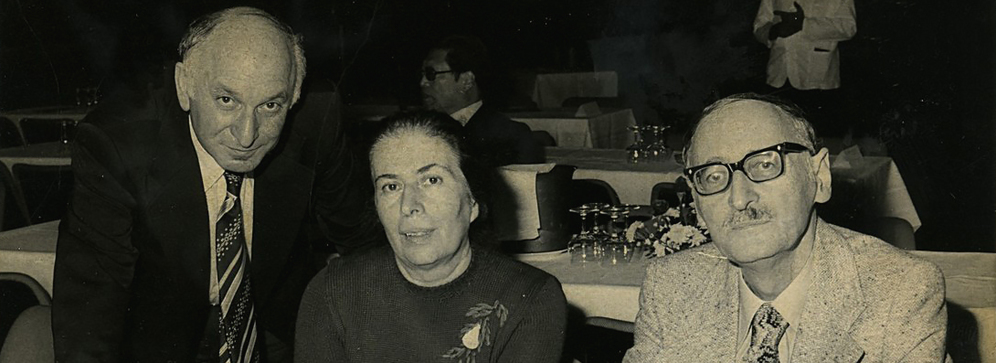

Ephraim II - Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia (1960-1972)

Despite this, virtually every Orthodox Church became a member of the World Council of Churches in New Delhi in 1962. Taking into consideration the inability of the Georgian Church to resist the Soviet nomenklatura with respect to enrolment, for the clergy it was obligatory to promote the interests of the Soviet state on the platform that the World Council of Churches provided. Despite the situation that existed in the Georgian Orthodox Church, however, during a visit to Paris in 1962, Patriarch Ephraim spoke of an increased number of the faithful in Georgia, who by the church leader’s estimate represented three quarters of the population.[39] Ephraim did not, on the other hand, talk about problems that existed in the church, or about the intensifying antireligious and atheist wave that it faced. The Patriarch’s emphasis of this piece of information serves as a good illustration of Soviet religious policy: there was to be an appearance that religious freedom existed in the Soviet Union in this period and that activity at an institutional level was not constrained. We can however say that at this time, the Georgian Orthodox Church as an organization stood at a low level in terms of the rights accorded to it, with no entitlement under legislation to make independent decisions. Patriarch Ephraim II spread Soviet views at the WCC, from censuring racism in the USA to rejecting the colonial repression of national liberation movements in Africa, and in the second half of his term as patriarch became an even better honed weapon of the Soviet authorities. Khrushchev forced numerous church leaders to conform to Soviet policy, while the church administration remained an obedient organ of this.[40] The process of the Soviet Union acquiring influence in the World Council of Churches began in 1961, when the Russian Orthodox Church joined the Ecumenical Movement, and was intensified from 1962 onward with the enrolment of the other Orthodox churches in the USSR, following which the views of the USSR began to be expressed on this international stage.

Conclusion

An analysis of Soviet religious policy reveals a number of factors and dimensions that defined this throughout its history, among which were an ideologized religious policy at a domestic level and a desire to strengthen the Soviet Union as a global hegemonic state at an international level. The issue of religion formed a constituent part of a Soviet ideological policy which at once encompassed politics, economics, and culture. An analysis of the approach adopted by the Soviet state to religious affairs must take into account its historical and social context, in which the enrolment of those churches in the Soviet Union into the Ecumenical Movement was a carefully considered step on the part of the nomenklatura. In parallel to intensifying an antireligious and atheist policy, the Soviet state attempted to display an inverted image of the USSR on the international stage, in accordance with which there was religious freedom in the Soviet Union, it was possible to carry out religious ceremonies, and the rights of the faithful were protected. The Council for Religious Affairs, which was attached to the Soviet Council of Ministers, considered it expedient to increase cooperation, through the churches of the Soviet Union, with the World Council of Churches, although this cooperation had little to do with the consideration of religious matters. As a result, the Georgian Orthodox Church found itself, together with the other Orthodox churches of the USSR, on the institutional platform of the Ecumenical Movement, which is a prominent example of the extent to which religious institutions were utilized as a tool of Soviet policy.

Translated by Geoffrey Gosby

Referenced Works

Anderson. J. 1994. Religion, state, and politics in the Soviet Union and the successor states. Cambridge University Press https://b-ok.asia/book/910149/a2fc23 (10.05.2022)

The Archive of the Academy of the MIA of Georgia, second section (the former “IMELi” Archive), collection 14, dossier 37, file №392

The Archive of the Academy of the MIA of Georgia, second section (the former “IMELi” Archive), collection 14, dossier 34, file №213

Corley, F. 1996. Religion in The Soviet Union. Macmillan press. London. UK. https://b-ok.asia/book/2577611/46d5a8 (22.04.2022)

The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 56

The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 57

The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 64

The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 81

Jones, S.F. 2013. Soviet Religious Policy and the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic church, from Khrushschev to Gorbachev. Publisher: Routledge

Hebly J. A. 2005. The state, the church, and the oikumene: the Russian Orthodox Church and the World Council of Churches, 1948-1985. Religious policy in the Soviet Union, red: Ramet. S https://b-ok.asia/book/852515/4d677c (15.05.2022)

Kalkandjieva. D. 2018. The Moscow Pan-Orthodox Council (8-18 July 1948). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326625018... COUNCIL_8-18_July_1948 (29.05.2022)

Kartvelishvili, M. 2019. sabchota religiuri politika da sakartveloshi misi asakhvis taviseburebebi 1953-1964 tslebshi [Soviet Religious Policy and Characteristics of its Manifestation in Georgia in the Years 1953-1964]. https://www.tsu.ge/assets/media/files/48/disertaci...

Kiknadze, Z. 2010. religiebi sakartveloshi [Religions in Georgia]. The Library of the Georgian Ombudsman https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/bitstream/1234/8483/1/R... (12.05.2022)

Pankhurst, J. 2012. Religious Culture: Faith in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. University of Nevada, Las-Vegas. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewconten... (29.05.2022)

Ramet. P.S. 1993. Religious policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press. file:///C:/Users/GeoComputers/Downloads/Religious%20Policy%20in%20the%20Soviet%20Union%20by%20Sabrina%20Petra%20Ramet%20(z-lib.org).pdf (25.05.2022)

Sawatsky. W. 1976. Secret Soviet Lawbook on Religion. Religion in Communist Lands, volume 4. file:///C:/Users/USER/Downloads/09637497608430788%20(1).pdf (22.05.2022)

Tooley, Mark. 31 March. 2010. World Council of Churches: The KGB Connection https://juicyecumenism.com/2010/03/31/world-counci... (12.05.2022)

U.S 86 TH Congress House Comittee on Un-American Activities - Crimes of Khrushchev. file:///C:/Users/USER/Downloads/The%20Crimes%20of%20Khrushchev%20(%20etc.)%20(z-lib.org).pdf

Vardosanidze, S. 2017. sakartvelos martlmadidebeli samotsikulo eklisiis astslovani matiane (1917-2017ts.ts.) [A Hundred-Year Chronical of the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church (1917-2017)]. Tbilisi: The Georgian University

Vardosanidze, S. 2007. sruliad sakartvelos katolikos-patriarki utsmidesi da unetaresi eprem II

(1960-1972 ts.ts.) [His Holiness and Beatitude Ephraim II, Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia (1960-1972)]. https://www.allgeo.org/index.php/ka/1554-ii-1960-1... (22.04.2022)

Walters. P. 2005. A survey of Soviet religious policy. Religious policy in the Soviet Union, ed.: Ramet, S.P. https://b-ok.asia/book/852515/

[1] Kiknadze, Z. religiebi sakartveloshi [Religions in Georgia]. p.137

[2] Anderson. J. Religion, State, and Politics in the Soviet Union and the Successor States. p.81

[3] Ibid. p.81

[4] Ibid. p.41

[5] Ibid, p.11

[6] Ibid, p.38

[7] Ibid, p.41

[8] Corley, F. Religion in The Soviet Union. p.259

[9] Vardosanidze, S. sruliad sakartvelos katolikos-patriarki utsmidesi da unetaresi eprem II (1960-1972 ts.ts.) [His Holiness and Beatitude Ephraim II, Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia (1960-1972)]

[10] Sawatsky. W. Secret Soviet Lawbook on Religion. p.28

[11] Ibid. p.28

[12] Kartvelishvili, M. sabchota religiuri politika da sakartveloshi misi asakhvis taviseburebebi 1953-1964 tslebshi [Soviet Religious Policy and Characteristics of its Manifestation in Georgia in the Years 1953-1964]. p.144

[13] U.S 86th Congress House Comittee on Un-American Activities. Crimes of Khrushchev. p.2

[14] Ibid. p.14

[15] Ibid. p.3

[16] Hebly, J. A. The State, the Church, and the Oikumene: the Russian Orthodox Church and the World Council of Churches, 1948-1985. Religious policy in the Soviet Union. p.105

[17] Jones, S.F. Soviet Religious Policy and the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church, from Khrushchev to Gorbachev. p.293

[18] Walters, P.A. A survey of Soviet religious policy. p.23

[19] Jones, S.F. Soviet Religious Policy and the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church, from Khrushchev to Gorbachev. p.297

[20] Hebly, J.A. The state, the church, and the oikumene: The Russian Orthodox Church and the World Council of Churches 1948-1985. p.112

[21] Corley, F. Religion in The Soviet Union. p.291

[22] Tooley, M. World Council of Churches: The KGB Connection

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] The Party Archive of the Central Committee of the Georgian Communist Party, collection 14, dossier 34, file №213, p.2

[27] The Party Archive of the Central Committee of the Georgian Communist Party, collection 14, dossier 37, file №392

[28] Pankhurst, J. 2012. Religious Culture: Faith in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. p.16

[29] Vardosanidze, S. patriarkebi [The Patriarchs]. p.48

[30] Vardosanidze, S. sruliad sakartvelos katolikos-patriarki utsmidesi da unetaresi eprem II (1960-1972 ts.ts.) [His Holiness and Beatitude Ephraim II, Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia (1960-1972)]

[31] The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 64, p.1

[32] The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 56, p. 4-11; 14-18

[33] The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 56, p.1

[34] The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 81, pp.10-13

[35] The Georgian Central Archive of Contemporary History, collection 1880, dossier 1, file 57, pp.14-18

[36] Vardosanidze, S. sruliad sakartvelos katolikos-patriarki utsmidesi da unetaresi eprem II (1960-1972 ts.ts.) [His Holiness and Beatitude Ephraim II, Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia (1960-1972)]

[37] Vardosanidze, S. sruliad sakartvelos katolikos-patriarki utsmidesi da unetaresi eprem II (1960-1972 ts.ts.) [His Holiness and Beatitude Ephraim II, Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia (1960-1972)]

[38] Kalkandjieva. D. 2018. The Moscow Pan-Orthodox Council (8-18 July 1948). p.6

[39] Jones, S.F. Soviet Religious Policy and the Georgian Orthodox Apostolic Church, from Khrushchev to Gorbachev. p.297

[40] Ibid. p.298