Geopolitics and Soviet Rhetoric through the Prism of Soviet Georgian Periodicals (1936-1941)

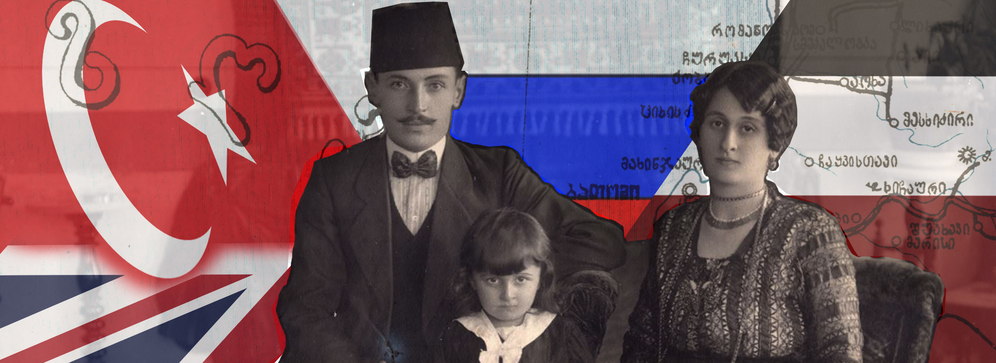

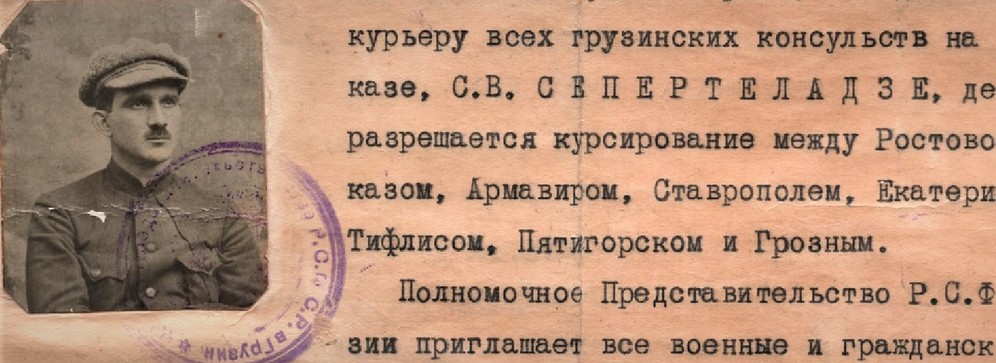

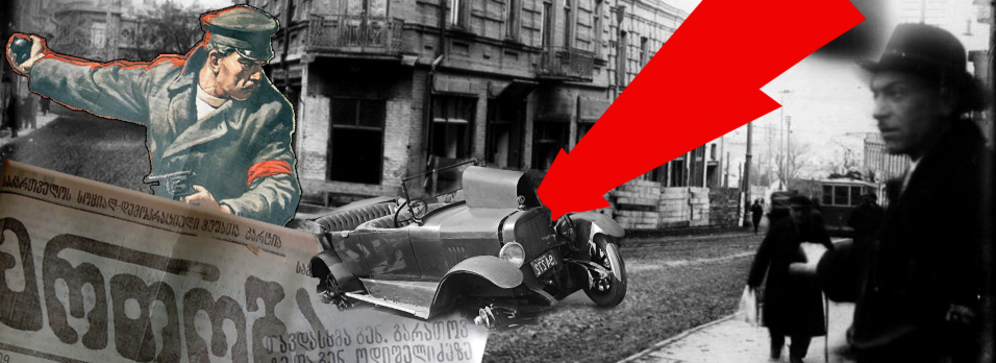

Not long after Russia commenced its assault on Ukraine, videos and articles began to appear on social networks emphasizing similarities between Putin and Hitler, and between Russian and German fascism. Yet while it is certainly the case that Hitler has come to represent a sort of iconic aggressor, such that any politician who appears before us with aggressive rhetoric is sure to be equated with him, Putin is not Hitler’s historical successor; it is more on the lathe of Soviet policy that the language of war and policy that we are hearing from Russia today has been turned. It is Soviet rhetoric that will be examined in this article through the prism of Soviet Georgian periodicals. With reference to the newspapers komunisti [The Communist] and literaturuli sakartvelo [Literary Georgia], we shall view geopolitical events as illuminated through a Soviet prism. What picture of these developments would the Soviet citizen have had in the second half of the 1930s? Who were enemies and who were friends? How did this rhetoric change when the Soviet Union switched sides and formed an alliance with Germany? And what was the nature of Soviet war rhetoric as the USSR was itself seizing neighbouring states?

David Low - The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (Political Cartoon) BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Geopolitics and the Soviet Press

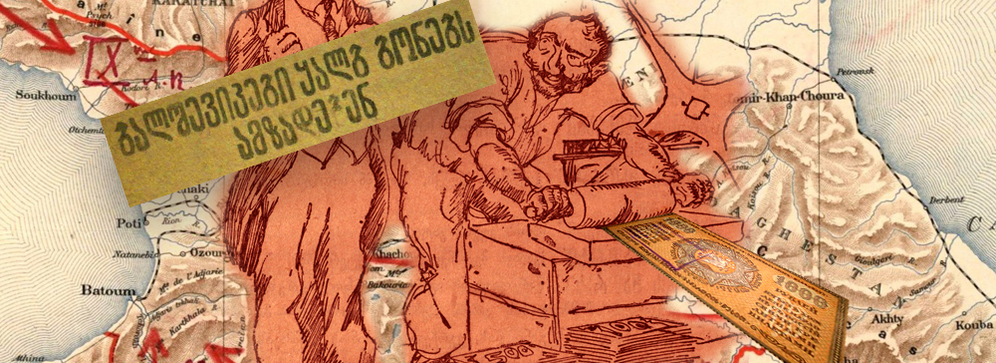

While a striking feature of the Soviet press is its propagandistic coverage of events, of comparable significance is what was not covered, what was not written, and what was not published. This constitutes a sort of informational absence, or information that, for the Soviet reader, did not exist – events about which the Soviet citizen had no awareness, or at most a vague one. One of the most powerful aspects of propaganda was precisely this informational vacuum. Let us take as an example an article from the 23 February 1938 edition of The Communist. The headline of the article is “Hitler’s Speech at the Reichstag” and the text of the article reads: “Yesterday, Hitler delivered a speech at the Reichstag.” Neither the text of the speech nor its content is provided; there follow other articles from the foreign press in which Hitler’s speech is criticized.

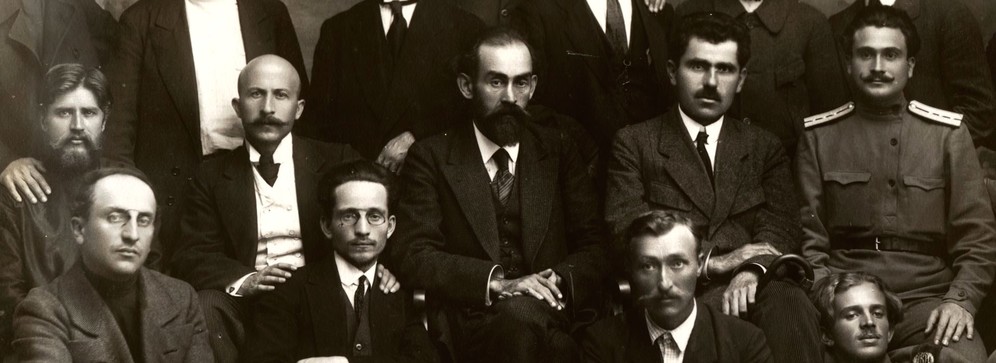

The informational vacuum is perceptible in the visual aspect of the press as well. This was focused entirely upon the Soviet space: great leaders, Soviet heroes, revolutionaries, and Stakhanovites were all that the reader of the Soviet press saw. Even when articles addressed geopolitical events, the visual material provided did not move beyond the borders of the Soviet Union. Germany, which the Soviet press vilified constantly, remains entirely invisible. Yet Soviet propaganda succeeded remarkably well at ensuring that the enemy’s image was simultaneously clear and indistinct. Clear, because images of the enemy were clearly provided everywhere, and indistinct because the enemy remained an image; that is, a portrayed rather than an actual one. This was also the case when the reporting did not concern mythical “enemies of the people” but more tangible, geopolitical entities; this is how Hitler is portrayed in the article “katsichamia” [The Cannibal], for example:

“A low, sloping forehead, small eyes, an inelegant nose, wide cheekbones, a facial expression that clearly reveals a person incapable of self-control, a person mentally unwell… Hitler’s voice is intolerable; it brings to mind the hoarse barking of a dog that gradually turns into a deafening yapping… He is coarse and foolish… Hitler hates all the people of the Earth: he is gladdened by the tormenting and annihilation of others”.[1]

Hitler, caricature by The Kukryniksy

It is clearly of no relevance what Hitler looked like in reality; rather, in the words of Umberto Eco: “The enemy must be ugly because beauty is identified with good”.[2]

Neither was the Soviet citizen able to view their allies clearly. Their gaze had always to be directed inside the Soviet Union; this moreover most likely made it easier to create the image of an enemy from former allies where this was required.

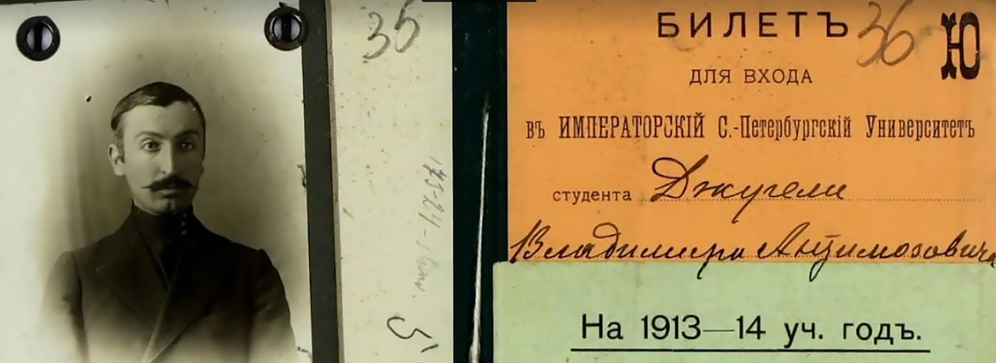

The interchangeability of allies and enemies was nothing unfamiliar to Soviet geopolitical reality – to a Bolshevik-socialist country surrounded by capitalists and fascists. Until 1939, the foreign policy pursued by the Soviet Union was quite consistent: it was the policy of a peacekeeping role, which was probably an apt diplomatic strategy for a country in a process of fundamental reorganization which could ill afford the luxury of international adventurism. The Soviet Union’s peaceful diplomacy was managed excellently by Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet people’s commissar of foreign affairs, who would probably have made a good democratic diplomat had he not been the representative of a totalitarian regime. This most westernized of the Bolsheviks tirelessly came forward with peace initiatives at the League of Nations and at any other international conference. A large number of his speeches focused on encouraging collective security (a concept which remains highly relevant today) and censuring fascism. Indeed, these speeches and the Soviet position were often even the most adequate in the struggle against the aggressors when compared with the policy of appeasement pursued by England and France. The Soviet Union condemned Italy’s war in Ethiopia, and the press naturally also tirelessly opposed the expansionist power at its borders – Japan – which had started a war with China; we also read numerous articles about the cruelties of Franco’s “fascist pack” and their military failures. Most importantly, the Soviet press was unsparing in its use of epithets in relation to the Soviet Union’s future ally, Germany. The headlines of the articles alone make it abundantly clear how extensive were anti-German attitudes: these include such examples as “The Wave of Fascist Terror in Germany”, “Yet Another Abomination among Fascist Germany’s Exploits”, and “The Wicked Anti-Soviet Campaign in Germany,” to name only a few. The Soviet press is filled with headlines of this nature until 1939, when Molotov and Ribbentrop concluded their pact. We read about the latter of these figures some three years prior to this:

“…To strengthen his own authority in the eyes of the English and accelerate the drawing of England’s ruling circles into his nefarious plans, Mr Hitler has taken the latest step of appointing an evildoer and bloodthirsty warmonger known the world over – von Ribbentrop – as Germany’s ambassador in London, as an individual who will attempt more brazenly and shamelessly to implant the notions of Germany’s “righteousness” and “historic mission” into English society.”[3]

Georgy Chicherin and Maxim Litvinov - People's Commissars for Foreign Affairs in the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s.

It ultimately came to appear that Ribbentrop had achieved this task in the Soviet Union, although prior to that point, anti-German and generally anti-fascist attitudes had been reaching ever new heights in all directions, as is characteristic of a totalitarian regime. In 1938, Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky appeared on Soviet screens – a film in which the Russian leader heroically defends Novgorod from the Teutonic hordes. It was impossible for a Soviet citizen watching this film not to turn their mind to the possibility of war with Germany. According to Orlando Figes:

“…the film’s plot showed such clear parallels with the Nazi threat that this impression did not subside even after the signing of the German-Soviet treaty of 1939.”[4]

Episode from Eisenstein's film "Alexander Nevsky"

An anti-fascist campaign was kindled among writers too. Evenings “against fascism and imperialist war” were held at the Georgian Writers’ Club. The 30 November 1938 edition of Literary Georgia included an article with the headline “The Georgian Intelligentsia Expresses its Concern and Indignation in Relation to the Persecution of the Jews in Fascist Germany”. In the article, the Georgian writers Shalva Dadiani, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, Simon Chikovani, and others condemn Germany’s antisemitic actions and, by contrast, heap praise upon the Soviet “state, founded upon the people’s idea of brotherhood, and its helmsman.” While the writers were likely more sincere in their condemnation of fascism than they were in their praise of the Soviet Union, at this time, in the words of Akaki Bakradze, writing was “not a matter of talent, or of thought, but propaganda.”[5] The totalitarian machine directed this propaganda unremittingly against internal and external enemies, which in many cases were connected. One of the charges levelled at repressed individuals was their having worked as agents for fascist countries and committed non-existent acts of sabotage, which served “in one shot” to destroy saboteurs internally and to draw attention to external threats. The danger of war from Europe or from Asia was growing ever more real, and against this background, heroism-filled articles about the Red Army grew ever more common. A defensive campaign was gathering pace in all directions, and writing is once again highly interesting in this regard. The call to create tavdatsviti literatura or “defensive literature” appeared in Literary Georgia and grew ever more urgent. What is the meaning of “defensive literature”? In the article “The Tasks of Defensive Literature” we read that:

“We describe as defensive literature specifically those works which directly address problems relating to the defence of the socialist fatherland and portray for us the role of the Red Army and its people in the civil wars, in collision with the Capitalist armies and in the process of building socialism.” [6]

The lavish praise which writers were to devote to the Red Army would probably serve it well later on; before then, however, the Union would still have to make a settlement with the “warmongers” and become their accomplices in crime.

Although the Soviet Union had no natural ally, its interests coincided with those of England and France; in particular, none of these nations desired a new world war. While it was true that England and France stood in the vanguard of the capitalist empire, which contradicted Soviet ideology, Stalin from the beginning acknowledged geopolitical reality and embarked upon a pragmatic diplomatic course. The reader of Soviet periodicals is left with the impression that a counterweight to the bloc of benighted, fascist countries is provided by the civilized world led by England, France, and, first and foremost, the USSR. In contrast to fascism, England and France were democracies, albeit bourgeois democracies. Though there are some articles which make surveys of economic crises and the exploitation of workers in capitalist countries, it can be said that there is no article to be found in periodicals in the years 1936-1938 which criticizes Anglo-French imperialist policy; to the contrary, Soviet newspapers often base their reporting on the press of these two countries, and what is written in London and Paris is accorded some authority in Moscow as well. In the article: “The Times against German Fascism”, for example, it is stated that the English press “is opposing as one the aspirations of the German fascists”.[7] The Soviet Union was not alone in the vanguard of the Soviets’ battle with fascism.

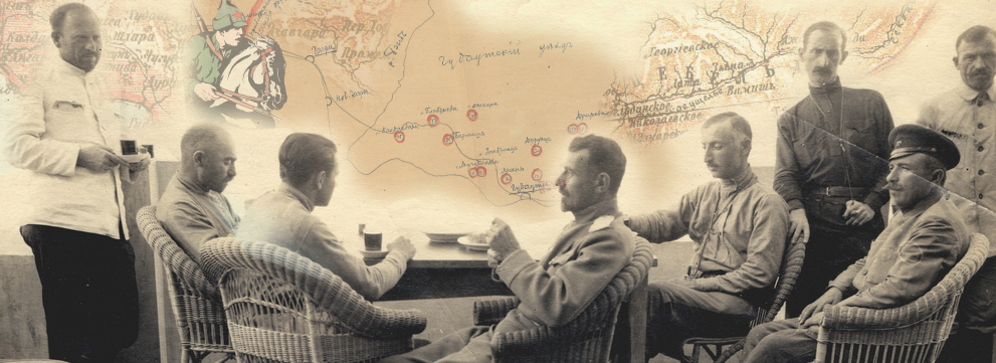

Stalin in fact attempted to achieve a greater closeness with the West during this period. A pact of mutual assistance was first signed with France in 1935 and then ratified in 1936, as the French nonetheless showed no great enthusiasm for it. The objective of the pact was to contain Germany, but in the West and in England especially, the containment of communism was no less of a preoccupation. In England, it was Germany which was seen as the performer of this role. Hitler for his part made masterful use of this situation, playing it excellently as a diplomatic card in his public speeches when it was necessary for the English to be mollified. This complex geopolitical situation was naturally painted in black and white by the indoctrination-obsessed Soviet press, and the official narrative of events contradicted by nobody. There was however at least one man who was able to think and to speak freely, and it was one of his public speeches that set a new course for Soviet foreign policy.

A New Course

In a speech delivered at the 18th Soviet Communist Party Congress on 10 March 1939, Stalin spoke on the subject of aggressors and “warmongers”. Although Italy, Germany, and Japan remained aggressors as before, this time the USA, England, and French were unable to escape the great leader’s wrath either. Stalin rebuked these nations specifically for their policy of non-intervention and inciting war.

“It is in their interests, should Japan begin a war against China, Germany, against the Soviet Union, and so on, that these nations should grow ever weaker in fighting one another. These “warmongers” will then emerge upon the stage with a peacemaking initiative so that they can dictate “their conditions” to the war-weakened participants. An inexpensive and fine idea!”[8].

Stalin went on to characterize the chief task of foreign policy as one of exercising caution not to allow “warmongers, who are accustomed to inducing others to do their difficult work, to drag… the country into conflict.”[9] Though the West was attempting to drag the Soviet Union into war, Stalin very significantly stated that the dangerous political game that they had begun with a “non-intervention policy” could end in a serious defeat. It later transpired that this statement had been correctly understood in Berlin.

Stalin took Soviet diplomacy in a new direction, and naturally the Soviet press too was instantaneously transferred onto new tracks. Articles were written about changes in foreign policy which tirelessly quoted the great leader and thanked him for his “wise policy”. Criticism of England and France also appeared. The reaction of these countries to the Anschluss had been insignificant, and they had offered the Sudetenland, with its crucial fortifications and mineral wealth, to Hitler on a platter. Litvinov’s constant reminder that nothing could be achieved by making concessions to the aggressor had become “the voice of one crying in the wilderness”. Furthermore, they had abandoned democratic Czechoslovakia directly to the aggressor, then confronted a far stronger Germany over Poland, which more closely resembled a military dictatorship. Although it was imperative for Hitler to be stopped at some point, by the time this was realized in the West it turned out that the diplomatic flirting between Berlin and Moscow, in which the two had just become involved, had gone too far. On 23 August 1939, the two powers signed a pact of non-aggression.

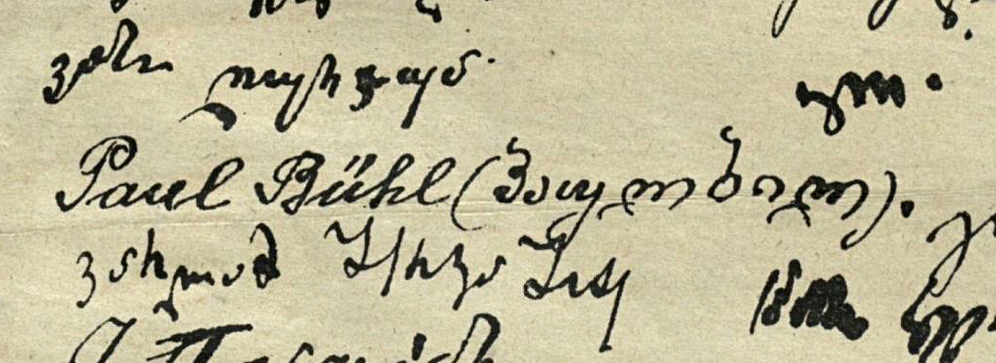

The negotiations were carried out on the Soviet side by a new people’s commissar of foreign affairs, the Germanophile Molotov; Litvinov, who was of Jewish heritage, had been removed from his post. The Soviet rhetoric about fascist Germany, the sworn enemy of the peace-loving, changed in the space of a day. On 26 August, each clause of the pact was published in the press; the newspapers portrayed it as a logical continuation of the Soviet Union’s peaceful policy. The secret part of the pact, “On Spheres of Influence”, which best of all demonstrates the nature of this “peaceful policy”, naturally went unpublished. A speech delivered by Molotov was printed in the press on 2 September:

“Indeed only yesterday in our foreign relations we were enemies; today though, circumstances have changed, and we are enemies no longer.”[10]

Molotov goes on to claim that peace between Germany and the Soviet Union would anger only the “warmongers”, for “they are just as much enemies of peace as all other instigators of war in Europe.”

The tone of this changed propaganda spread once more to every sphere. Stalin’s beloved Alexander Nevsky disappeared from screens. In a new plot, it was now British spies whom Soviet heroes were obliged to confront. It is significant that in 1940, in place of films that were anti-Nazi allegories, the half-Jewish Eisenstein was obliged to bring Hitler’s beloved Die Walküre to the stage of Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre.[11] Together with the disappearance of anti-fascist rhetoric, the German press grew increasingly important. Whereas previously, when the foreign press was cited, London had always been the foremost source, Berlin now took its place. It is against this background that the war with Poland is covered. Whereas previously, the Soviet press had written endlessly of the fascists’ military failures, the emphasis was now on the rapidity of the German advance and of Poland’s collapse. Events reached the point that, during the partition of Poland, a new “German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty” was signed. It is significant that prior to this, when the pact was being formulated, Ribbentrop had wished for the pact to contain some mention of German-Soviet friendship, which Stalin had rejected “in consideration of the fact that Berlin and Moscow had previously reviled one another”.[12] By the partition of Poland, however, the two nations were already accomplices in crime, so that little short of a friendship existed between them. Amid this sycophancy with Berlin, the discreditation of bourgeois democracies gathered pace. In a speech by the People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs at a session of the Supreme Soviet on 31 October 1939, which was as usual printed in the newspapers the following day, Molotov’s pre-declared assault on the bourgeois empires featured Germany portrayed in the role of their victim:

“…it is known that during these last few months, such notions as “aggression” and “aggressor” have acquired a concrete new meaning. It is not difficult to appreciate that we cannot now use these concepts with the same meaning that we did, for example, 3-4 months ago. Now, if we speak of Europe’s great states, Germany is in the position of a state which is endeavouring to end the war as soon as possible and achieve peace, while England and France, which only yesterday boasted of opposing aggression, are proponents of continuing the war and opposed to the conclusion of peace. As you can see, the roles have changed.”[13]

Is this really the voice of the same nation which called upon England and France to make an uncompromising stand against fascism? Yet for the Soviet leader, this change in nature was of no consequence; the most important thing was that at this stage, Stalin thought himself in the most advantageous position possible. In his view, so long as England, France, and Germany were embroiled in a lengthy and exhausting war, he would be able to strengthen his position in the East. Stalin was mistaken, however.The alarm caused by the lightning speed of Paris’ fall is expressed tangibly, albeit indirectly, in the press. Soon after this, Germany once again and more so than ever before had to be presented as a monster in the Soviet imagination, and one led by a “cannibal”. Prior to this, however, it was necessary for the USSR’s position in eastern Europe to be reinforced.

The Soviet Approach to War Propaganda

The Soviet press showed little favour towards its neighbouring states. The Baltic republics, Finland, and especially Poland were objects of reproach from the very beginning. Foreign policy followed the German line: “The Fascist Terror in western Ukraine”, “The Provocative Address of Poland’s (or Finland’s) Military Pack” – such were the rebukes issued against them in Soviet newspapers. Generally speaking, for the Soviet press, Poland was a fascist state that belonged to the same club as Germany and Italy. Discussing the dreadful economic situation in capitalist and fascist countries, the Soviet press reports:

“The allies and lackeys of Hitler and Mussolini, the Pans of Poland included, have no desire to lag behind them. Fascist Poland can rightly be considered one of the foremost capitalist states in terms of the number of its poor and the extent of their poverty.”[14]

The following year, in 1939, the “Pans of Poland” stood before the German threat. Now portraying Poland as a victim of fascism, the Soviet press was vociferous about “German Fascist Outrages in Danzig”[15] and “Anti-Polish Speeches in the Fascist Press”.[16] As is well known, however, this was not the final position that the Soviet press would adopt.

The assault on Poland began on 1 September, although the Soviet Union did not join it until 17 September. Though the Germans reproached them for this, this delay was necessary in order to create the myth that Comrade Molotov made public on the radio on 17 September, and which was immediately printed in the newspapers, when he began speaking about the “weakness of the Polish gentry” and their “essential helplessness”:

“The Polish state and its government essentially no longer exist… Poland has transformed into an opportune arena for all manner of contingencies and unanticipated developments which could present a threat to the Soviet Union… The Soviet Government cannot be expected to take an indifferent stance towards the fate of brother Ukrainians and Belarusians who live in Poland and were hitherto in the position of peoples without rights, and who have now been abandoned to their fate.”[17]

National security and coming to the aid of their fellow peoples were the mythical motive of the Soviets for seizing Poland. Together with Molotov’s words, the newspapers report on rallies – not rallies against the war, but rallies at which “the whole Soviet people fervently hail Stalin’s wise policy”. In an address, one ardent Stakhanovite passionately shouts:

“I do not have the words to express the torrent of joy that the news that we have received today has unleashed within us. Units of our powerful Red Army have been commanded to go forth into the territory of western Ukraine and western Belarus and to assist our brother workers there...”[18].

This was not the sincere position of just one individual, of course, but had to be the voice of every Soviet citizen; this was what the collective opinion had to be. It was in a similar way that in 1940, the Red Army was greeted in the Baltic countries with applause, jubilant cries, and flowers by the liberated masses, while the ruling kleptocratic pack fled as fast as they were able. It was in this way that the Red Army was greeted everywhere that it triumphantly entered. An unsuccessful war, on the other hand, required a different sort of propaganda.

No sooner had Poland been seized than it became Finland’s turn. Molotov had already stated in a speech given on 31 October that relations with Finland were in an “extraordinary situation” due to “the growing influence of “third states””. Leningrad, the USSR’s second city after Moscow, was only some 32 kilometres from the Finnish border. With war raging in Europe, urgent security measures needed to be taken. Molotov went on to reproach Finland for its independence and preach about the tolerant nature of Soviet policy:

“It must be said that no government in Russia other than the Soviet government can reconcile itself with the existence of an independent Finland at the gates of Leningrad.”[19]

Finland’s great neighbour did not intend to encroach upon its independence; a significant change in the border would be sufficient. The Finns revealed themselves to be uncompromising, however, and the result was the outbreak of war one month later. The “Winter War” began on 30 November and ended on 13 March, by which point the Red Army had sustained enormous losses. Despite these, on 14 March the Soviet press reported on a peace treaty and the successful settlement of the issue. It also wrote that:

“English and French imperialist circles had been encouraging Finland, as they had been Poland and other states, to make war with the Soviet Union, promising “guarantees” and assistance in this war…”[20]

After describing the Mannerheim Line, Molotov announces that “the hostile actions carried out in Finland show us that Finland… had already transformed in 1939 into a ready-made military platform for third states to use to attack the Soviet Union.”[21]

Njet, Molotoff!/No, Molotov! - A Finnish Folk Song

This had also complicated the war. Together with Finland, the Red Army clashed with “the united forces of the imperialists, including England, France, and others.” It was for this reason that losses were great: fewer than 49,000 on the Soviet side, and more than 60,000 on the Finnish side. Soviet losses in reality exceeded 126,000 and were six times the equivalent Finnish figure;[22] suppressing this western intervention had cost the Red Army dearly.

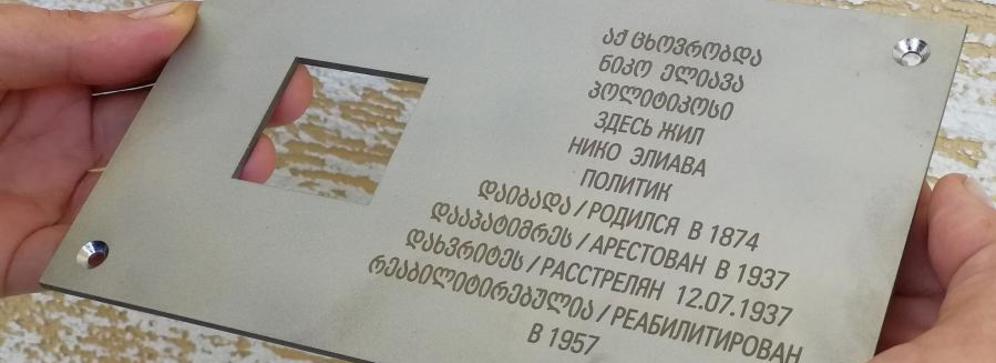

In Place of a Conclusion

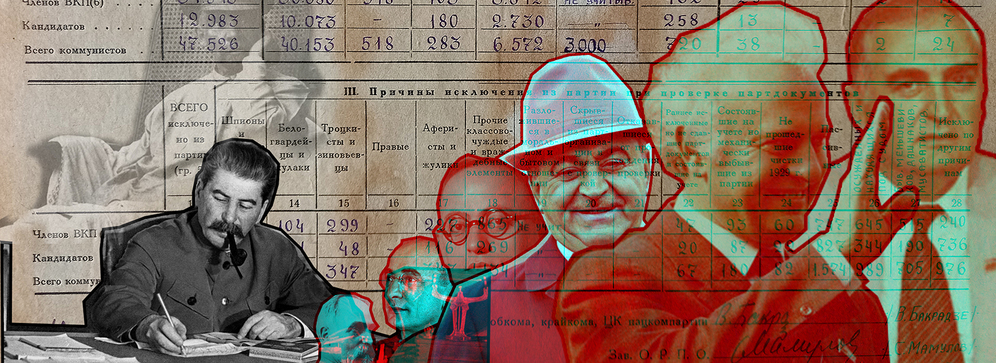

In 1937, an Eric Arthur Blair was fighting on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War, where he witnessed first-hand the brutal crimes of the Communists and the NKVD who represented the “peace-making” USSR. His experiences left an indelible impression upon him, and subsequently upon his written works, which he published under the pseudonym “George Orwell”. Had Stalin’s totalitarianism become irreversible, things would most likely have ended in Orwell’s dystopian world; a world in which past and present are altered endlessly through systematic modification of the press and other documents. All of those events would probably have disappeared from old newspapers which proved irreconcilable with the status quo – those shameful pages reporting that the Soviet Union had befriended “abominable fascist Germany” overnight, for example. Individuals removed by Stalin from his circle disappeared from photographs and other documents in just the same way; the constant transformation of reality was probably Soviet totalitarianism’s most fundamental characteristic.

Fortunately, Orwell’s world did not come into being, but the legacy of the Soviet period still exists. The language and mythology of war employed by the Soviet Union are alive once again, and have returned with their familiar tone to a new reality. Russia once again tells us in the Soviet style of “a special operation”, of “oppressed brother peoples”, and of a Ukraine “transformed by the west into an anti-Russian bridgehead”. This Soviet legacy is by no means exclusive to Russia, however: its shadow stalks all post-Soviet countries and, it could be said, the world as a whole. It is for this reason that ongoing reflection upon Soviet experiences provides us with important parallels at the levels both of geopolitics and of our everyday lives.

Translated by Geoffrey Gosby

Referenced Works

- Bakradze, Akaki, mtserlobis motviniereba [Taming Literature], The State Museum of Georgian Literature, 2019, p.58

- “germanuli pashistta utsesobani dantsigshi” [German Fascist Outrages in Danzig], The Communist, 1939, No.79, p.44

- Eco, Umberto, Inventing the Enemy and Other Occasional Writings, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012, p.5

- “tavdatsviti mkhatvruli literaturis amotsanebi” [The Tasks of Defensive Literature], Literary Georgia, No.21, 1939, p.1

- Ehrenburg, Ilya, “katsichamia” [The Cannibal], Literary Georgia, 1941, No.29, p.1

- komunisti [The Communist], No.204,1938, p.3

- komunisti [The Communist], No.58, 1939, p.1

- komunisti [The Communist], No.201,1939, p.1

- komunisti [The Communist], No.215,1939 p.1

- komunisti [The Communist], No.252, 1939 p.1

- komunisti [The Communist], No.60, 1940 p.1

- komunisti [The Communist], No.74, 1940, p.1

- “mteli sabchota khalkhi mkhurvelad miesalmeba brdznul stalinur politikas” [The Entire Soviet People Fervently Welcome Stalin’s Wise Policy], The Communist, 1939, No.215, p.1

- “taimsi germaniis pashizmis tsinaaghmdeg” [The Times against German Fascism]. The Communist, No.215, 1936, p.1

- Figes, Orlando, natashas tsekva – rusetis kulturuli istoria [Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (Georgian translation)], Ilia State University, 2019, p.433

- “pashisturi presis antipolonuri gamosvlebi” [Anti-Polish Speeches in the Foreign Press], The Communist, 1939, No.154, p.4

- Sharashenidze, Tornike diplomatiis istoria 1920-1939 [A History of Diplomacy from 1920-1939], Bakur Sulakauri Publishing, 2021, p.257

- Kenez, Peter, A History of the Soviet Union from the beginning to the end. Second edition, University of California, 2006

- Gorge Orwell, British author, George Orwell | Biography, Books, Real Name, Political Views, & Facts | Britannica 7/21/2022

[1] Ilya Ehrenburg, “katsichamia” [The Cannibal], Literary Georgia, 1941, No.29, p.1

[2] Umberto Eco, Inventing the Enemy and Other Occasional Writings, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012, p.5

[3] “mshvidianiobis mtrebi” [The Enemies of Peace], The Communist, 1936, No.247, p.2

[4] Orlando Figes,natashas tsekva – rusetis kulturuli istoria [Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (Georgian translation)], Ilia State University, 2019, p.433

[5] Akaki Bakradze,mtserlobis motviniereba[Taming Literature], The State Museum of Georgian Literature, 2019, p.58

[6] “tavdatsviti mkhatvruli literaturis amotsanebi” [The Tasks of Defensive Literature], Literary Georgia, No.21, 1939, p.1.

[7] “taimsi germaniis pashizmis tsinaaghmdeg” [The Times against German Fascism]. The Communist, No.215, 1936, p.1

[8] The Communist, No.58, 1939, p.1

[9] Ibid., p.2

[10] The Communist, No.201, 1939, p.1

[11] Peter Kenez, A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End, University of California, 2006, p.137

[12] Tornike Sharashenidze, diplomatiis istoria 1920-1939 [A History of Diplomacy from 1920-1939], Bakur Sulakauri Publishing, 2021, p.257

[13] The Communist, 1939, No.252, p.1

[14] The Communist, 1938, No.204, p.3

[15] “germanuli pashistta utsesobani dantsigshi” [German Fascist Outrages in Danzig], The Communist, 1939, No.79, p.44

[16] “pashisturi presis antipolonuri gamosvlebi” [Anti-Polish Speeches in the Foreign Press], The Communist, 1939, No.154, p.4

[17] The Communist, 1939, No.215, p.1

[18] “mteli sabchota khalkhi mkhurvelad miesalmeba brdznul stalinur politikas” [The Entire Soviet People Fervently Welcome Stalin’s Wise Policy], The Communist, 1939, No.215, p.1

[19] The Communist. 1939, No.252, p.1

[20] The Communist, 1940, No.60, p.1

[21] The Communist, 1940 No.74, p.1

[22] Peter Kenez, A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End, University of California, 2006, p.133