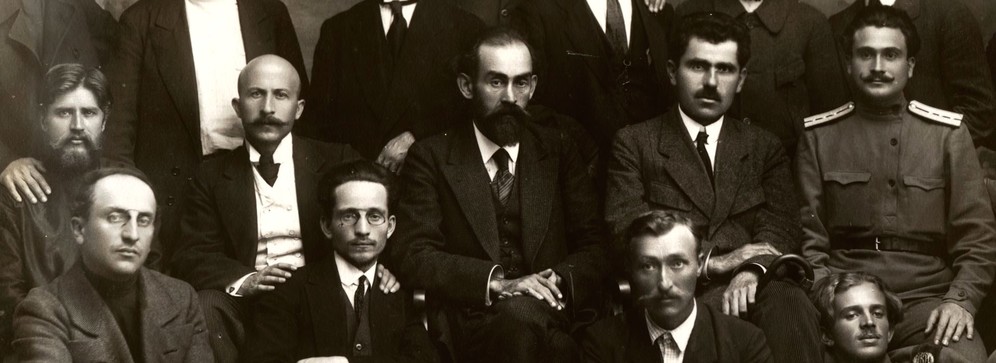

Hygiene became a subject of Soviet propaganda from as early as the Russian Revolution. The majority of this propaganda was visual, comprising posters, pamphlets, leaflets, animated films, newspapers, and even plays; theatres of sanitary culture existed at the end of the 1920s in Moscow, Leningrad, Tbilisi, Odesa, Luhansk, and other cities. Both the plays and other visual propaganda addressed such subjects as healthy living, sexually transmitted diseases, alcoholism, the physical education of the proletariat, and caring for mothers and children.

The principal objective of propagandists working in this subject matter was to successfully communicate specific appeals, which were intended to facilitate indoctrination in Soviet ideology, to people with varying ethnic, religious, and other backgrounds. One of the aims of this article is to describe the tendencies associated with these efforts, and how the propagandists attempted forge a new Soviet citizen through the practice of hygiene.

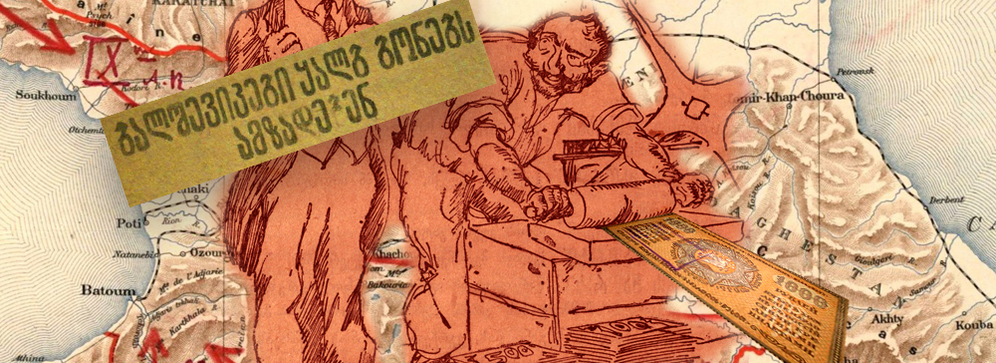

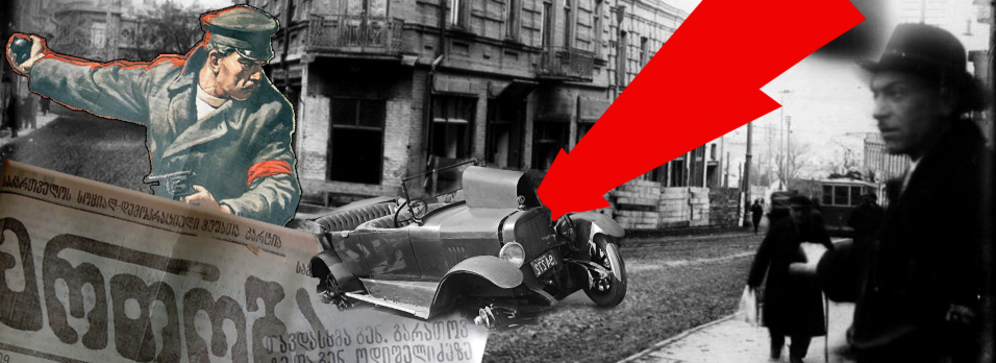

The posters printed in the Soviet Union, which began to appear in its very first years, are distinctive in terms of their colourfulness, their general style and design, and their language and themes. Those researching Soviet propaganda can find a number of examples by using internet search engines or browsing various online groups. The key themes featured in this means of mass communication are easy to identify; neither is it difficult to recognize, by noting the date of each example’s publication, that the posters are characterized by well-defined subject matter which is imbued with the historical context of a specific span of time in the Soviet period, or with aspects of policy that were important for the Soviet leader of that time. Among the many posters of this kind, which are associated with such periods as that of collectivization, the Second World War, and the Cold War, we also come across posters which are concerned with hygiene, the body, health, exercise, and the upbringing of children. The vast majority of these posters were created or printed in the first half of the Soviet period, from immediately after the Russian Revolution to the Second World War, and in the first stage of the latter in particular.

It was with an interest in these posters that my interest in Soviet hygiene propaganda began. Why might it have been deemed desirable for so many versions of posters to be printed as to how a mother should feed her child, how a citizen should wash their hands, and, more generally, what sort of a body the new Soviet citizen should have?

One thing that was clear from the outset is that what transformed the Soviet Union (and not only this country) into a totalitarian regime was the monitoring and regulation of every aspect of citizens’ lives. That personal hygiene should have featured among such aspects is no great surprise. Neither, moreover, should we disregard the consideration that concern for citizens’ health, especially against the background of epidemics or in the aftermath of revolutions or wars, is in itself no negative thing. What is striking in this case is the discourse produced through Soviet mass communications about the body, health, and hygiene which, through Soviet propaganda, implied indoctrination in Soviet ideology, more distinct examples of which we see in Soviet periodicals and other forms of propaganda.

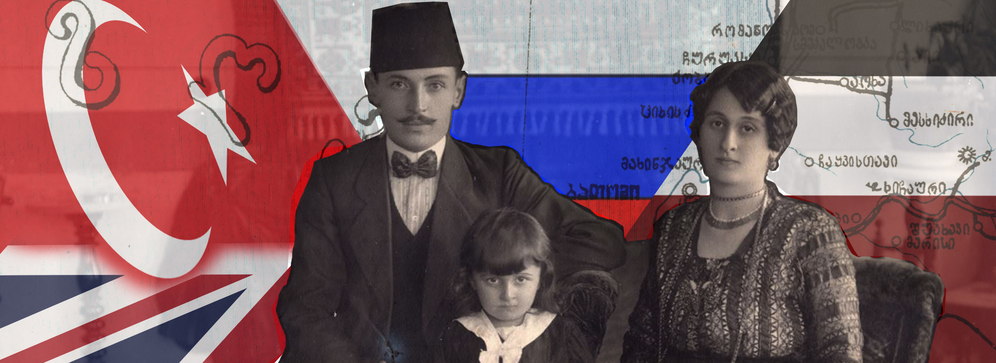

The focus of my research, which will be discussed in this article, is therefore as follows: How did the hygiene propaganda of the early Soviet period shape discourse about the body? For its part, how did Soviet ideology manifest itself in this discourse, and in what relation did it stand with authority? Finally, how was this policy manifested in Soviet Georgia, and to what extent did it share the language and symbolism manifested in the discourse that was produced centrally?

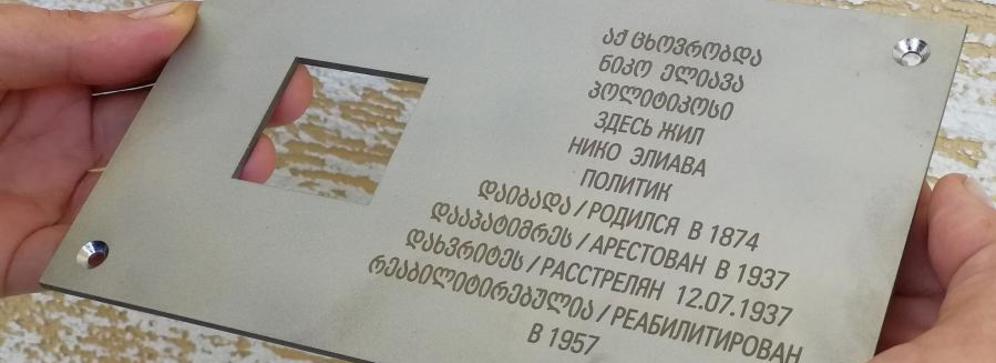

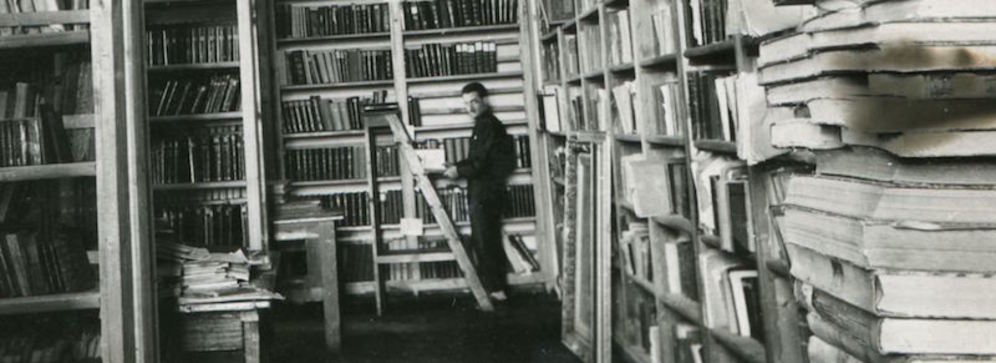

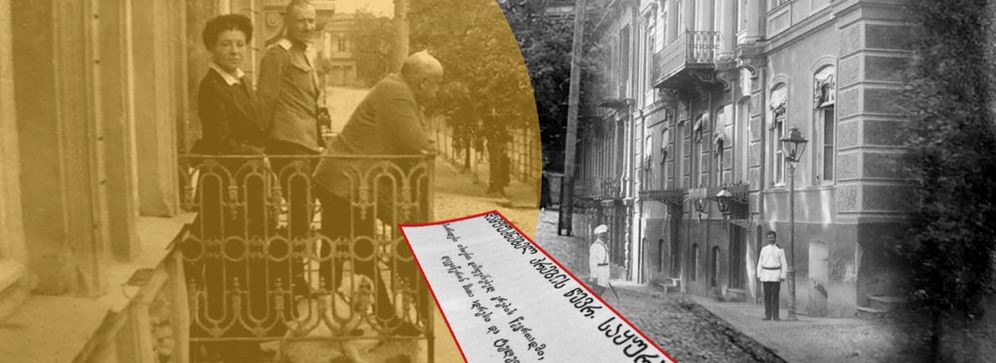

In the course of my research and to respond to the questions posed above, I worked closely with related materials held at the Georgian National Library: The Soviet magazine saunje [Treasure-House] (1924-1927), which is directly concerned with the subject of hygiene; related articles from periodicals (for example, the newspaper komunisti [The Communist]); educational textbooks on hygiene for both schools and institutions of higher education; Soviet routines for hygiene and sanitation; and short routines of a comparatively small size in pamphlet format intended for school pupils or other target groups, or for Soviet citizens more generally.

The Georgian National Archive also contains the following collections relating to Soviet hygiene: The collections of the Republican Scientific Institute for Labour Hygiene and Occupational Illness of the Georgian SSR Health Ministry; the collection of the Theatre of Sanitary Culture of the Health Department of the Executive Committee of Tbilisi City Council; the collection of the Scientific and Research Institute for Sanitation and Hygiene of the Georgian SSR Health Ministry; and the collection of the Union Scientific Institute for Labour and Hygiene attached to the Georgian SSR People’s Commissariat for Labour.

In my analysis of these materials I naturally placed importance on their comparison with examples from visual propaganda.

Why Propaganda?

One of the objectives of hygiene-related Soviet propaganda was “to raise awareness among citizens”. The citizen made aware of hygiene-related matters was considered “developed”. Such matters were addressed in a section of the magazine saunje titled “ganvatavisuplot khalkhi tsrurtsmuneobisgan” [Let Us Liberate the People from Superstition], in the content of which it is readily apparent that communist ideology is manifested beyond the subject of hygiene. The dichotomy of “developed-backward” is equated to one of “cleanliness-dirtiness”, while those things considered to be superstitions include features and notions of local culture, which are associated with the tsarist and older regimes. An example of the subjects addressed in this section is those infectious diseases which were known by the name batonebi (“lords, masters”) and traditional folk treatments for them; these were deemed unacceptable for the Soviet citizen, for to conceive of these diseases in such a relation to oneself was considered a vestige of the tsarist regime. In connection with the notion of backwardness the journal often discusses the mountainous population of Georgia; the tradition of bosloba[1] related to pregnancy and childbirth, for example, as well as the traditional Khevsuretian house are cited as examples of living conditions harmful to the citizen.

An important issue for Soviet propaganda was that of the protection of mothers and children. In addition to describing in detail in these works how a mother should care for herself during pregnancy, and then for the child, in articles written on these matters we can also discern a central strategy to which Soviet propaganda linked this subject. Several articles begin with the consideration that for centuries, people had believed that a danger was posed to the world by great numbers of people, but that development and political cataclysms (by which the First World War and the Russian Revolution are meant) had shown the chief problem to be falling demographic trends, so that ifone wished for a state to develop, thrive, and be strong, an essential condition for this was population growth. The problem was then that, as a result of ignorance, many died during pregnancy, and the newborn mortality rate was also high; for this reason, one of the principal “missions” of hygiene propaganda was to increase the population, for which a healthy, strong body was indispensable.

It is not the purpose of this article to refute that addressing this subject in Soviet hygiene-related posters or other forms of mass communication addressed specific problems and formed a part of Soviet “preventative medicine”, which represented a certain vision as to their resolution (the effectiveness of which is to a great extent undetermined). Neither is the discussion of such a policy in terms of propaganda an assessment based only on personal perception.

Aside from those researchers who have worked on this subject to date, Soviet authors themselves employed the term “propaganda”: the primary materials consulted in the course of my research confirm that the subject of hygiene formed part of the propaganda of the early Soviet period. The magazine saunje, for example, which was published monthly in Georgia from 1924-1927, defines its importance as a publication sometimes as “sanitary-popular”, and sometimes as “sanitary-propagandistic”. “A permanent magazine is needed which will transform into a true cultural source and inexhaustible “treasure-house” of sanitary education”,[2] we read in the magazine’s very first edition.

In order to discuss the manufacture of a discourse about the body intended to inculcate these ideas into citizens using the example of hygiene, it is essential also to examine the objectives or essence of propaganda in the Soviet Union in itself. The visual aspect of this propaganda was of particular importance, which was naturally for specific reasons: a large part of the population was illiterate, and the Soviet Union comprised a large span of territory populated by groups that were diverse in terms of ethnicity, religion, and several other factors, and so it was important that the central messages of propaganda should reach every citizen in such a way that they were able to recognize themselves as their intended recipient.

Sources: https://www.facebook.com/sovietvisuals/photos/chil...,

https://gallerix.ru/storeroom/1973977528/N/1624162...

Researchers of Soviet propaganda identify several important aspects as explanations as to its essence; these can include the objectives of arousing hatred toward the enemy; consolidating an alliance with allies; cooperation with “neutral entities”, and the demoralization of the enemy. In this process, new symbols, rituals, and visual concepts were manufactured which facilitated not only the consolidation of absolute authority, but also the changing of messages.[3]

Authors writing on the objectives and results of propaganda discuss the invention of real or artificial social groups and the symbolizing of their unity, as well as the consolidation and legitimization of existing institutions, statuses, and relations and the attempt to instil new beliefs, value systems, and behaviours.

While a concern for health is rarely associated with the revolutionary years, Vladimir Lenin often called attention to this subject even during the war. Between 1919 and 1923, three quarters of the Russian population were starving, with the result that waves of typhus, Spanish flu, chicken pox, and bubonic plague became all the more devastating. Between the years 1914 and 1921, a large proportion of the population either became ill or died. This was the state of affairs inherited by the Bolsheviks, and for Lenin, the restoration of Russian power and the creation of a model state entailed a transformation of the population – “the struggle for socialism is the struggle for health.”[4]

In addition to this the Bolsheviks faced the significant problem of legitimizing their authority, for which their principal weapon was propaganda. While propaganda was especially important for all totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century, the challenge facing Soviet leaders and their attitude towards propaganda were entirely unique, in that the Bolshevik regime was the first to make the objective of its propaganda the ushering forth, by means of political education, of an entirely new society and its constituent entities which would be acceptable to their vision of a utopia. Their self-confidence that the audience of this propaganda comprised bodies that were either ignorant or polluted by an incorrect ideology was transformed by them into a source of their legitimacy,[5] with the implication that those at the centre of authority were entitled to regulate absolutely every space of the Soviet citizen’s life, including even the most personal; in another respect, the reproducibility of propaganda would enable them to found the legitimacy of their own authority upon foundations already prepared in this way. Every institution of power was involved in this endeavour.

The early Soviet period is characterized by a veritable explosion in propaganda. A number of journalists and academics who travelled to the Soviet Union during this period write about the extraordinarily large number of posters that entirely covered urban spaces. Assessments regarding this trend differ among these authors as well, although we can discern from their writings the scale that Soviet propaganda assumed, in addition to the forms and language that it employed. Such an accent on visual propaganda itself – aside from this being easier to communicate to the majority of the population than propaganda in the form of the printed word – they associate with the great importance of images in Russian culture and history.

Source: https://www.vzsar.ru/special/2014/11/28/v-yaslyah-...

Furthermore, the religious disposition of the population meant that icons were something very familiar to a large part of it. By conferring a new content and ideology upon familiar forms, propaganda sought to achieve its principal objective of inducing the population to see itself reflected in its messages and images and thereby forming new, Soviet values; symbols and forms bearing positive connotations were to propel the Soviet citizen towards the new contents that propaganda bestowed upon them.

It was in this way that the Soviet conception of good and bad, acceptable and unacceptable, and clean and dirty was formed, and everything in turn translated into the strict Soviet dichotomy of hero and enemy.

Taking the example of hygiene, it is the aim of this article to demonstrate how the Soviet authorities attempted to implement this approach, and what forms, language, and symbolism they selected both centrally and in Georgia.

What themes did Soviet hygiene address?

The forms of Soviet propaganda were highly diverse. In addition to posters and forms of print media, cinema, theatre, lengthy school textbooks, and small pamphlets for distribution to the population were also weaponized in this way.

As various historians and researchers have worked on the discourse of hygiene and caring for the body in a general Soviet and especially a Russian context, I will focus upon this discourse within Georgia. It should however also be noted that the majority of authors who have written about the importance of hygiene have focused only on the context of the 1920s and the period following the Russian Revolution, while the materials that I have studied encompass the 1930s and the period of the Second World War. As such, these provide information on the discourse during this span of time and a means of comparing those changes and tendencies that accompanied the changing historical context, as well as how these are reflected in available narratives about hygienic practice.

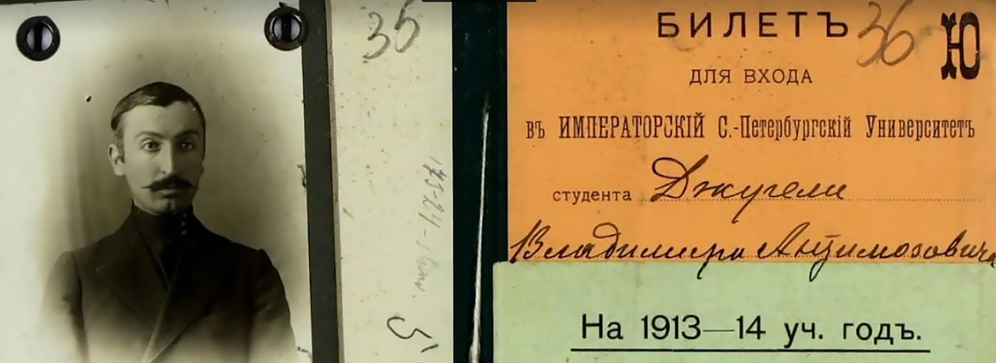

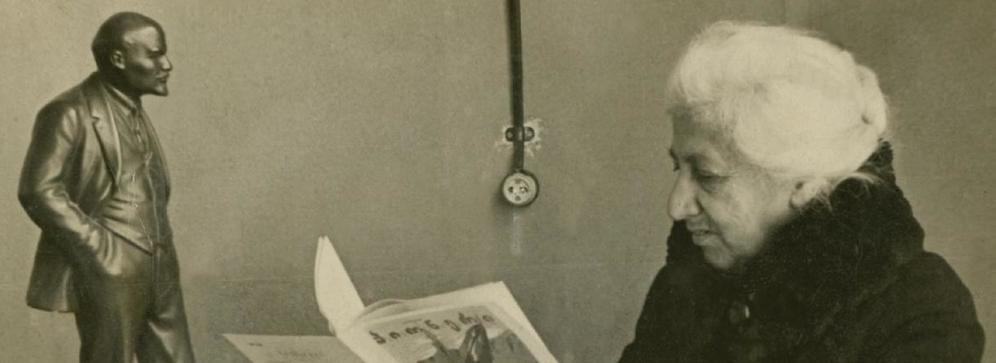

One especially interesting example from 1920s Georgia is the previously discussed magazine saunje, published 1924-1927. The editor and writers of the magazine were doctors by profession, and the monthly magazine directly reflects those principal hygiene-related themes which were significant for the Soviet Union as a whole.

In the magazine’s first issue, its editor explains the publication’s objective: “Just as its mother’s breast and the milk that it provides are best for feeding a small child and the first source of life, so the language of the motherland is the only correct path and means to educate the working people. […] A permanent magazine is needed which will transform into a true cultural source and inexhaustible “treasure-house” of sanitary education! […] The editorial board calls upon all workers in the medical and sanitary field to form a professional alliance and demands from them tireless cultural work for the restored health and wellbeing of the people.”[6]

The writers of the magazine’s articles focus on the work of sanitary organizations; there is also a separate section about “victims of the profession”, which in every issue begins with Lenin’s words about the importance of the profession of doctor for the state (after that of the soldier).

The principal messages of the magazine addressed medical treatments, the maintenance of hygiene, a healthy lifestyle, maintaining a healthy home environment, and the fight against illnesses. They demonstrated the attitude of the Soviet authorities towards what for them were unacceptable bodies, and on the other hand what could be acceptable. Everything that did not fit into ideologized theories of hygiene was presented to society as a danger, and those who did not follow these rules were accordingly offenders who represented a threat not only to themselves, but also to those around them and to the existence of the Soviet state itself. Such offenders could include a mother who did not rear her child in accordance with Soviet values, as well as users of alcohol or tobacco, or those who did not follow the proper rules when cleaning their homes.

One of the most important and interesting subjects was that of “social diseases”. The articles written on this attest to the extent to which hygiene propaganda strays beyond simply “caring for the health” of the population, and to which the authorities manufactured a discourse about what was acceptable and what was unacceptable. “Aside from the many illnesses which hasten towards the human body and harm its health, also highly widespread are various kinds of moral deficiencies which seize control of individuals unnoticed and distort their nature […] Social… diseases destroy families, corrupt society, and undermine the wellbeing of the people.”[7]

We also encounter articles about the dangers posed to the Soviet citizen by poetry or excessive consciousness, or the nature of the Soviet conception of the “degenerate”. Each of these is deemed to be the result of the historical context or bourgeois ideology: “Those children who were conceived during difficult historical eras and times of trouble clearly display various illnesses and disorders of the nervous system following birth.”[8]

We also often encounter descriptions of the traditional customs of Georgia’s mountainous population as examples of backwardness, a lack of development, and superstition; their living conditions and traditional buildings as unacceptable, as these result in a lack of sunlight which causes individuals to become backward and undeveloped. Such people are themselves unworthy of the Soviet Union and cannot fit into the utopian model that the Soviet Union has engendered.

One medium of propaganda that I have already mentioned is that of film showings and theatres. We also frequently encounter opinions about their importance and necessity in pamphlets published about hygiene. “Theatres of sanitary culture”, which were directly associated with hygiene, existed in the republics of the Soviet Union, including in Tbilisi. The objectives of the theatre’s plays, and of the theatre itself, can be gathered from short articles published in the newspaper komunisti which provide a primary source for analysing their intent. Here we find calls for the legitimization of the system, together with the demonization of what had existed hitherto, as well as an impression as to how the concepts of “clean” and “dirty” bodies were formed in addition to attempts, via propaganda, to regulate not only the body, but also the morals of the Soviet citizen. In the academic literature we find information about the activities of similar theatres in other cities of the Soviet Union. The plays predominantly took the form of mock trials held to pass judgment on individuals who had violated standards of hygiene. The trials were so realistic that members of the audience often made quite violent attempts to intervene in them, and playing the role of the “offender” came ultimately to be associated with considerable danger, to the extent that actors often avoided taking on these parts .[9]

Source: https://historyofknowledge.net/2019/05/20/hygiene-...

From the 1930s onward, the principal form and tendencies change. The consolidation of Stalinism and the state of confrontation with fascist Germany which arose likewise manifest themselves through the example of hygiene, while language and forms change and take on a more militaristic character. If previously, western systems provided the major examples for Soviet writers to follow, confrontation with the west was now also perceptible in the methods and theories of hygiene espoused.

It appears unusual at first glance that the biological doctrine of eugenics,[10] which is associated with right-wing totalitarian systems and was treated with importance in Nazi Germany, also formed a component of social hygiene in the Soviet Union, even though the attitude of Soviet theorists of hygiene towards eugenics was different and nonhomogeneous. Such views enjoyed greater popularity in the 1920s, although they differed from the standard, western model, introducing the concepts of “negative” and “positive” eugenics, of which the second of these was acceptable for Soviet ideology because, unlike in western eugenics, the chief challenge and chief strength of the desirable species was not only to be better able to survive than others, but also to reproduce on a greater scale. Although this theory came to be incorporated into the Stalinist five-year plans, at the beginning of the 1930s “eugenics” became unacceptable in any form, due on one hand to its association with Nazi Germany and the western countries, and on the other to the unacceptability of Soviet theorists of eugenics to the regime following their subjection of the five-year plans to criticism.[11]

A conflict between these theorists and those of Soviet hygiene took place in Georgia as well, as attested in a textbook titled sotsialuri higienis dziritadi sakitkhebi [Fundamental Issues of Social Hygiene].[12] Published in the mid-1930s, this work focuses on the importance both of the “furious struggle between the classes” and of the confrontation with fascism. Its author criticises the use of principles of “eugenics” in hygiene, recounting the words of those Georgian scientists who were its proponents in the preceding decade. For the author, the fundamental problem lies in viewing diseases, the body, and treatment as a matter solely of biology; in their view, it followed from Marxist ideology that the social aspect was of far greater importance. This was on one hand a response to the tendencies in Germany, and on the other an emphasis of the importance of the social aspect of diseases. In accordance with ideology, “treatment” of this was a means of extending authority.

In the foreword to a small pamphlet published in 1941 titled daitsavit piradi higiena [Look after (Your) Personal Hygiene], we read that “At this time, when bloody international fascism threatens all of our achievements with fire and sword, the matter of strengthening the muscles of the Soviet individual is attributed the utmost importance. To the extent that the importance of physical and mental solidity faces every Soviet citizen alike, this booklet must likewise unquestionably be considered useful for our heroic Red Army, for only the individual equipped with sanitary culture can be a fit and fully performing fighter.”[13]

This is one clear example of the conferring of a militaristic significance on the body and the Soviet conception of it in the 1930s, and also demonstrates the relationship between the state, society, and the body of the individual.

Conclusion: The Hygienic Body in the Soviet Utopia

The regulation of Soviet bodies was a form of solution to those problems which faced the Soviet totalitarian regime following the Russian Revolution. Policy and propaganda in relation to hygiene, sport, and physical education transformed the bodies of Soviet individuals into bearers of an entirely political content which was to be loaded with ideological knowledge of a kind that was acceptable for the new Soviet citizen. Anybody who with respect to their own illnesses, lifestyle, or body was incompatible with such an ideological model was a priori the expression of another political order, “cleansing” from which, following the logic of the regime, was legitimate and acceptable.

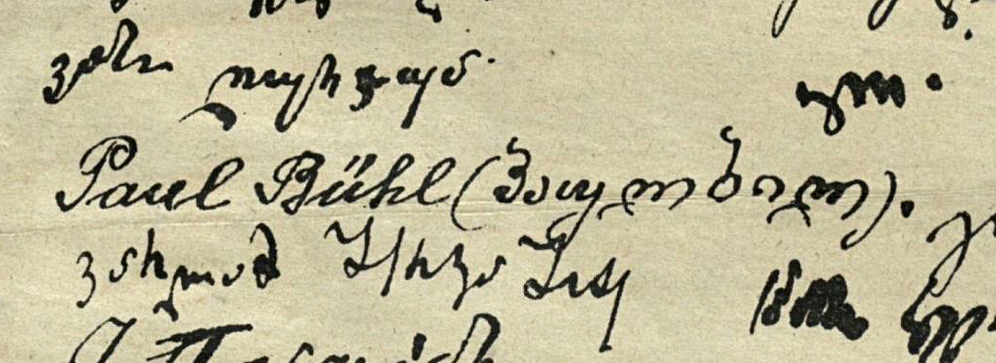

Source: saunje [The Treasure-House], No.4, 1925, p.16

Not only in Soviet sporting and hygiene policy but in that of other totalitarian regimes of the 20th century as well, the central entity was the metaphor of the body, the purpose of which was to transform the body into a collective, social organ. The point of departure for this objective was not the health of the individual, but their significance as a component part of the collective Soviet body. Caring for one’s own body is presented to us not as a right, but as a political duty of the Soviet citizen, including by Soviet theorists of hygiene. By their conception, the health and body of a person are important to the extent that these are linked to the health of their family and this with the health of society, which is in turn connected with the health of the people as a whole and ultimately with the health of the state and of humanity.[14] Such a characterization of hygiene is demonstrative of a relation between the system and the individual in which the question of the individual’s independent role, rights, and significance is eliminated.

For theorists of both the Soviet and the Nazi regimes, the body was a political space, and practice associated with it and its propaganda a form of indoctrination which was achieved by persuasion as to the absolute correctness (in the Soviet case) of Soviet concepts concerning the body, in addition to other, associated strategies. Such totalitarian regimes used hygiene to target the body as a path to reach citizens’ minds; physical and hygiene-related instruction strengthened patterns of thinking and inculcated characteristics that the regime required in order to realize its own utopia and to cement its own authority.

Translated by Geoffrey Gosby

Referenced Works

Bonnel, V. E., Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin. University of California Press, 1997

Hoffman, D., Bodies of Knowledge: Physical Culture and the New Soviet Person. Ohio State University, 2000

Jijadze, A., sotsialuri higienis dziritadi sakitkhebi [Fundamental Issues of Social Hygiene]. Tiflis State Publisher, Scientific Sector, First Section, 1935

Kenez, P., The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization 1917-1929. Cambridge University Press, 1985

Leuhrmann, S., “The Modernity of Manual Reproduction: Soviet propaganda and the Creative Life of Ideology”. Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 26, Issue 3, 2011, pp.363-388

Qorchibashi, G., saunje [The Treasure-House]. The United Council for Sanitary Education, Tbilisi, 1924-1927

Sherozia K., komunisti [The Communist]. The Central Body of the Georgian Communist Party and Bodies of The Tbilisi Committee and the Georgian Revolutionary Committee, Tbilisi, 1937

Starks, T., The Body Soviet: Propaganda, Hygiene, and the Revolutionary State. The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008

Unknown Author, daitsavi piradi higiena [Look after (Your) Personal Hygiene]. Sakmedgami, Tbilisi, 1941

[1] “bosloba” is mentioned several times in saunje as the key cause of health problems among women living in mountainous regions of Georgia; the tradition is explained in the magazine as “a deplorable custom in Mtiuleti, Pshavi, and Khevsureti” whereby women give birth without the supervision of a doctor (saunje [The Treasure-House], No.3, July, 1924).

[2] S.K., Editorial, saunje [The Treasure-House], No.1, 31 May, 1924, p.1

[3] Bonnel, V. E., Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin. University of California Press, 1997

[4] Starks, T. The Body Soviet: Propaganda, Hygiene, and the Revolutionary State. The University of Wisconsin Press, 2008

[5] Kenez, P. The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization 1917-1929. Cambridge University Press, 1985

[6] S.K., Editorial, saunje [The Treasure-House], No.1, 31 May, 1924, p.2

[7] S.K., “sotsialuri senebi” [Social Diseases], saunje [The Treasure-House], No.1, 31 May, 1924, p.5

[8] Gachechiladze, V., “deda da misi movaleoba” [The Mother and Her Duty], saunje [The Treasure-House], No.3, 30 July, 1924, p.18

[9] Starks, T., The Body Soviet: Propaganda, Hygiene, and the Revolutionary State. the University of Wisconsin Press, 2008

[10] A doctrine concerned with the improvement of human characteristics with the purpose of perfecting the human race through selectively breeding certain individuals. The term was proposed by the English eugenicist Francis Galton, who devised the principles of eugenics, in 1865-1869.

[11] Solomon, S. G. and Hutchinson, J. F., Health and Society in Revolutionary Russia. Indiana University Press, 1990

[12] Jijadze, A., sotsialuri higienis dziritadi sakitkhebi [Fundamental Issues of Social Hygiene], Tiflis State Publisher, Scientific Sector, First Section, 1935

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Kakhi”, “sakhalkho janmrteloba, rogorts mtavari amotsana sakhelmtsipo aghmsheneblobisa” [The Health of the People as the Primary Objective of the Construction of the State], saunje [The Treasure-House], No.1, 31 May, 1924, p.2